Against the background of two recent biographies, of V.K. Krishna Menon by Jairam Ramesh (A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V.K. Krishna Menon, Penguin, 2019) and of V.P. Menon by Narayani Basu, I wrote an article in OPEN magazine titled “A Tale of Two Menons”. See here. An earlier version is below:

Menon and Menon: Freeing and Integrating India

In the context of two recent and well-researched biographies, I compare the lives and characters of V.K. Krishna Menon and V.P. Menon, two influential men who helped shape independent India in their unique ways.

Introduction

Rise of Indians in government service

The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919, among other things, brought in pay parity between Indian and British government officials. By then, it was not a question of whether India would become independent but how long later. And also in what manner, and to what extent. With this, serving in India became less and less attractive to British officials, who started withdrawing. With fresh incumbents also coming down, their numbers began declining. This allowed Indian officials, including the non-ICS, to rise higher in the hierarchy. These were mainly from Bengal, Kashmir, the Kayasths, Tamil Brahmins, and Nairs from the Malabar District of the Madras Presidency. The last group went by various surnames, including Menon, Panikkar, and Pillai.

Nairs in government service

At independence, Nairs wielded immense clout in the corridors of power. They had come up through different routes. From the ICS, like NR Pillai, the first Cabinet Secretary, and KPS Menon, the first Foreign Secretary. So did many others, like N. Raghavan, MK Vellodi, and K. Ramunni Menon. They also came from the allied services such as Revenue, like KRK Menon, the first Finance Secretary.

Some others came through distinguished service with the States. Sardar KM Panikkar, who was Dewan of Bikaner, became a permanent representative to the United Nations. He became Ambassador to China, Egypt, and France, and a member of the States Reorganisation Commission. Dr. P.P. Pillai, the first Permanent Representative to the United Nations, came from an altogether different track. Among the first Indian doctorates in Economics, he was the first Indian to publish in an international Economics journal. He was also the first Indian to join the League of Nations. He later heading the Indian branch of the International Labour Organization for around 20 years.

Apart from those in high positions, the Central Secretariat had hordes of South Indians, mostly Tamil Brahmins and Nairs. When a department had too many Nairs, people jokde that it had Menon-gitis. But, that is not as creeping and debilitating as an incurable attack of TB, retorted the Nairs, in a not-so-veiled reference to Tamil Brahmins.

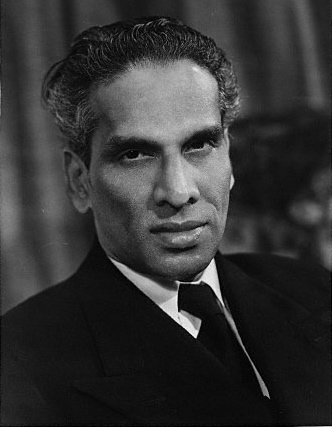

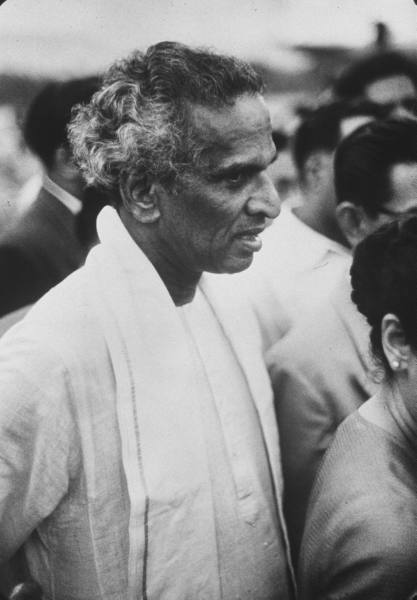

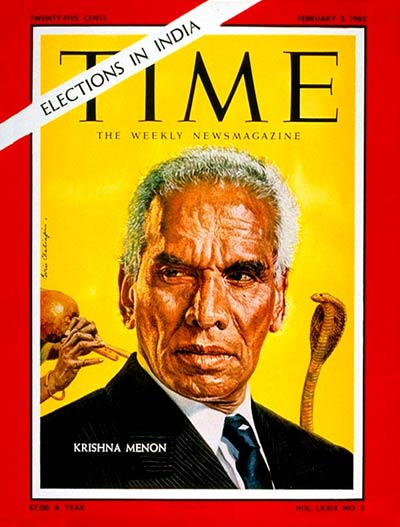

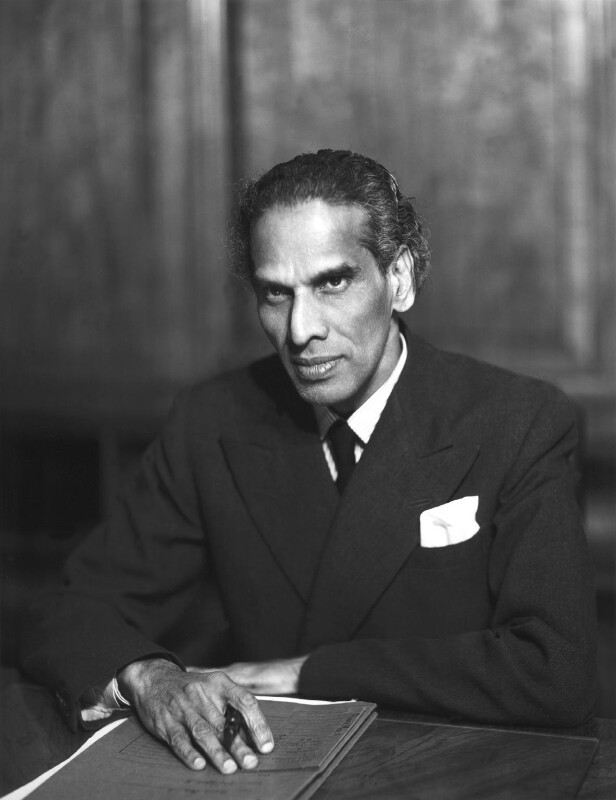

Two Menons

Of current interest are two other Menons who charted their unique paths: VK Krishna Menon and VP Menon. These largely forgotten men are back into limelight because of two recent biographies, one on VK by Jairam Ramesh[1], and on VP by his great-granddaughter, Narayani Basu[2]. People remember VK Krishna Menon today best for his tenure as the Defence Minister during the disastrous China War of 1962. They hardly remember his tenure as India’s first High Commissioner to the UK or his role as Secretary to the India League in the UK for over two decades.

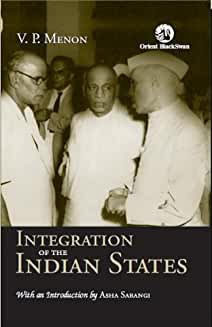

VP Menon was perhaps the only government clerk to work his way up, through sheer hard work and determination, to become a Secretary level official as Reforms Commissioner and Constitutional Adviser to three Viceroys (Lord Linlithgow, Lord Wavell, and Lord Mountbatten). After independence, he was also Secretary of the Ministry of States, assisting Sardar Patel in integrating around 565 native States with the Indian Union.

Similarities

No two men could have had so many similarities but also had several stark differences. Apart from being Menons, both were from the Malabar District of the Madras Presidency, VP from Ottapalam in Palghat, and VK from Panniankara near Calicut. Neither wrote an autobiography. But both left behind large volumes of paper. VP also wrote significant books of lasting importance. His books, ‘The Story of the Integration of Indian States’, ‘Transfer of Power to India’, and a thin volume on India’s Constitutional History, are so bereft of personal life details that they do not qualify as memoirs.

VP did not leave any letters of note, but VK left many. VK also wrote many pamphlets and reports, most during his India League days. VP did not have any biography before the one by Basu. VK had at least two in his lifetime, one by Emil Lengyel[3] and the other by TJS George[4]. VK was at his acerbic best when he told George: “Autobiographies are written by those who believe that the world is centred on them – and the world is not centred on any individual – and biographies are written by those who have nothing else to do.”

Visionaries

Both were great visionaries. In the early 1930s, VK called for a Constituent Assembly and made the first draft of the Preamble to the Indian Constitution. He provided the intellectual heft to India’s non-alignment and other foreign policy positions. As a Fabian socialist influenced by Laski and Russell, VK’s speeches on disarmament at the UN were prescient. He was the first to argue for recognizing Bangladesh and ending apartheid in South Africa. VK argued for nationalising banks at least 15 years before Indira Gandhi implemented it in 1969.

VK laid the foundation for India’s indigenous defence research and production capabilities, which his predecessors, including Nehru, had not considered. Morarji Desai scuttled his efforts to improve Defence preparedness, then Finance Minister, who argued for nonviolence and Gandhian values. VK insisted that India negotiate and settle its border dispute with China, which could have prevented the 1962 War. But, when Chou en Lai visited India in 1959, Nehru kept VK out of the negotiations. Yet, after the War, VK became the scapegoat for India’s humiliating defeat!

In the early 1950s, VK recommended three young economists in their 20s to Nehru, to do future work for the country. These were KN Raj, Amartya Sen, and Jagdish Bhagwati, a roll call of honour among Indian economists.

VP’s practical wisdom and foresight helped manage various ticklish issues and seeming deadlocks while integrating 565 native states with the Indian Union. VP convinced Mountbatten and Patel that partition was the only viable option. VK did the same with Nehru.

Both were persons of great integrity. In VK’s case, even his careless involvement in the Jeep purchase scandal did not mar his reputation for long.

Critics of Gandhi

Did the Nairs in service generally hold a critical view of Gandhi? One of the worst critiques of Gandhi was Gandhi and Anarchy written by Sir C Sankaran Nair. He remains the only Malayali to have been President of the Indian National Congress. His son-in-law, KPS Menon, would become the first Foreign Secretary.

Our two Menons were not different. Both were not wholly uncritical of Gandhi and seemed to have had an uneasy relationship with him. Both were close to and fiercely loyal to their political bosses: VK to Pandit Nehru and VP to Sardar Patel. At least in the case of VK, he often became a proxy for those targeting Nehru. VP attended Patel’s funeral privately even after being barred by Nehru. VK was the one who got Nehru’s books published and popularised them in the West, contributing in no small measure to building the international aura behind the name of Nehru.

Differences

But the similarities end there. Both were, literally, pheno-Menons in their unique way.

Early years

Born three years earlier, Vappala Pangunni Menon (1893-1965) was the son of a school headmaster from a lower-middle-class family. On the other hand, Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon (1896-1974) was the son of a wealthy lawyer whose maternal great-grandfather was a former Dewan of Travancore.

Both left their homes while still in their teens, never to return home much. VP was a school dropout who ran away from home after setting fire to his school to spite the teacher who had insulted him. He worked as a labourer in the Kolar Gold Fields and as a coolie, among other odd jobs in Mumbai. VK, on the other hand, was an eternal student. He followed a more conventional route. After studying at Presidency College, Madras, he went to London, where he studied under Harold Laski and others at the London School of Economics for ten years. He continued his education till the ripe old age of 38, when he was finally called to the bar.

Mentors

VK had influential mentors. The first was Annie Besant, the theosophist and educationist based in Madras, where he met her while still a student. She arranged to send him to the UK, where he continued for 29 years. The second was his Professor, Harold Laski, political scientist and Fabian socialist, for whose funeral he would lend the Indian High Commission’s Rolls Royce. VK also had eminent collaborators in Bertrand Russell, the philosopher, mathematician, pacifist, and Allen Lane, with whom he co-founded Penguin and Pelican books.

VP did not have a real mentor, though he had his lucky breaks. The story handed down to me was that VP’s most crucial break came while working as a punkah puller for a British officer, to whom he would volunteer comments on whatever he was working on. The precocious young VP’s observations must have impressed this unknown British official enough for him to recommend VP for a clerical job with the Government of India.

Personalities

The personalities of the two Menons also differed. VK was abrasive and did not suffer fools easily. A diplomat who was not diplomatic, he had no time for self-serving sycophants. He was also prone to depression, false modesty, self-pity, and writing suicidal notes. On the other hand, VP drew on his tact and diplomatic skills to get hundreds of Princely States to sign the Instrument of Accession to the Indian Union.

VK was a bundle of contradictions. The socialist and perhaps atheist entertained an enduring interest in astrology, forever troubling his sister to send him predictions from the local astrologer. He feared what would happen to the vast family’s land possessions if the communists were to implement land reforms. He also opposed the linguistic reorganisation of states for fear that a unified Kerala would become a bastion of communism.

Anecdotes

VP was an excellent mimic. In one of the meetings that Secretaries used to have (Remember the Yes Minister series), VP mimicked Nehru. In a subsequent meeting with the PM, Nehru observed in a grave tone, “VP, I believe you are a great mimic.” The culprit could have only been HVR Iengar, then Secretary to the PM. VP lashed out at whoever had carried it to Nehru in the next meeting, without naming anyone. That was the end of such meetings.

VK was a vegetarian and teetotaller known for his endless appetite for tea and biscuits. VP enjoyed his whisky. To create a wedge between VP and Sardar Patel, HVR Iengar once told Patel, Gandhian and teetotaller, that VP drinks. Patel picked up the phone, dialled Menon, and asked him what brand of whisky he drank. VP mumbled something and inquired why he asked. Patel replied, “I would like to recommend the same to some of your colleagues.”

VK’s best anecdotes involve his quick repartees. When told that the sun never set on the British Empire, he replied that it was because God would never trust the Englishman in the dark. This anecdote is now found to be misattributed to many others.

When Pearson Dixon, the British delegate to the Security Council, picked holes in VK’s language, VK retorted, “Sir, I can understand your difficulty in understanding what I have said; you picked up your English on the streets of London, I devoted several years of my life to learn it with the care and respect it deserves!” When Pakistan’s Muhammed Zafarullah Khan was going on about plebiscite in Kashmir, VK addressed the chair and said, “Plebiscite, Plebiscite, Plebiscite! Sir, ask this gentleman whether his country has ever seen a ballot box!” VP was not known for his repartees.

Personal lives

VK remained a bachelor, perhaps not so chronic, and a reluctant bridegroom, known for many affairs, mostly with non-Indian women. VP had a troubled married life, the first wife having left him and their two sons without a trace. After that, he lived with the wife of a friend and mentor from a different caste. His two sons never forgave him, maybe for not bringing their mother back into their lives.

Intellectual leanings

VK, though from an affluent background, had strong socialist leanings. He was even suspected by the British and Americans of being a closet communist sympathetic to the Russians. This was perhaps because he was closer to members of the Labour Party, which was more sympathetic to India’s demand for total freedom. Though from a humbler background, VP opposed Nehru’s socialist ideas, even joining the Swatantra Party founded by Rajaji, which had espoused liberal economic policies. In the process, he would be in the company of many royals with whom he had negotiated integrating into the Indian Union. He was even found tiger hunting with a few of them. The socialist that he was, VK was not known to have entertained the company of any Indian Royals.

VK was a great orator, and the seats in the UN General Assembly filled up when he was scheduled to address it. Among his classic speeches are those on disarmament and the famous eight-hour speech on Kashmir, the longest ever at the UN (until recently), during which he fainted. VP was a typical civil servant, seen and not heard. So, there are no known public speeches of VP.

Electoral life

While in the UK, VK was elected as borough councillor of St Pancras, London. It conferred on him the Freedom of Borough, the only other person so honoured being Bernard Shaw. VP never contested elections. VK contested thrice from Bombay, winning twice in 1957 and 1962 and losing in 1967. He went on to win from West Bengal in 1969 and again from Trivandrum. He thus became probably the first and only person to contest and win from three corners of the country.

Relations with the bureaucracy

VK and VP were victims of the ICS’s disdain for the not-twice-born. But, at least VK had many admirers among civil servants. Jairam Ramesh’s biography of VK quotes letters by Nehru to CD Deshmukh, the Finance Minister, defending Krishna Menon. These must have been in response to what Deshmukh himself had written to Nehru about. Deshmukh studied Natural Sciences at Cambridge, while VK studied Economics at the London School of Economics and the University of London, among many other things that he dabbled in while in London. Therefore, it was only natural that VK considered himself more competent to hold views on economic matters, notwithstanding Deshmukh’s earlier stint with the Reserve Bank of India as its first Indian Governor. Then, there were VK’s ego clashes with Sanjeevi Pillai of the Intelligence Bureau and the old Jeep scandal that kept rearing its head at inappropriate times.

Diplomatic life

VK was not diplomatic, but no other Indian reached the heights of success in diplomacy as VK had. He was the original Kissinger, nicknamed Formula Menon, the one people reached out to to find a way out of an international deadlock. As a roving ambassador, his larger-than-life presence loomed over numerous meetings in Geneva and issues across countries and regions, including Cyprus, Korea, Nepal, Suez Canal, Indochina, Algeria, Hungary, and Formosa (now Taiwan). His successes included the many meetings with Chou en Lai in Geneva and successfully negotiating the release of US pilots held by China, which even Dag Hammarskjold, then UN Secretary-General, could not manage. That begs the question, would he not have made a great UN Secretary-General? Or even better, a great Foreign Minister for India in place of Nehru, who, as the Prime Minister, also held the portfolio throughout his tenure of seventeen years?

Defence Minister

Contributions

As Defence Minister, VK was an institution builder, establishing the National Defence Academy, Defence Research and Development Organization, the Border Roads Organization, Sainik Schools, etc. His other accomplishments included the acquisition of INS Vikrant, India’s first aircraft carrier; taking over of the Mazgaon Dockyard, Mumbai, and Garden Reach, Kolkata; launch of the indigenously manufactured Avro 748, paving the way for Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd., and establishment of the Heavy Vehicles Factory at Avadi. He was thus the original “Make in India” man. As Defence Minister, VK completed one of the unfinished jobs of integration of India by annexing Goa, which earned him the epithet “Goa Constrictor”[5]. It was a sign of his integrity and the success of the non-aligned stance that the Americans, including President Kennedy, wanted VK to be eased out, probably under pressure from the defence production lobby.

India China War

Notwithstanding his achievements, VK remains forever associated with perceived lapses as a Defence Minister in the India-China War. Jairam Ramesh attributes this flawed narrative to army officials writing the early books on the war. VK never had a rosy relationship with them. Chief among them was General Thimayya, who frequented the British High Commission, where foreign liquor was freely served.

A significant revelation in Jairam Ramesh’s book is the revelation that Malcolm MacDonald, the British High Commissioner, recorded that in such meetings, Thimayya would bad mouth both his bosses, VK and the PM, even making the egregious claim that the former was plotting a coup. This was nothing short of high treason. Thimayya should have known better that Krishna Menon, having lived in London for three decades, would have known these comments from his sources.

What is also less remembered is that India’s lack of defence preparedness owed a lot to the Finance Minister, Morarji Desai, and Members of Parliament like JB Kripalani, both of whom argued against allotment of funds for Defence in the name of nonviolence, Gandhian ideology, etc. After the Chinese fiasco, the same persons were questioning without any sense of morality why Indian forces were ill-prepared.

MKK Nayar, a first-batch IAS officer, wrote in his memoirs that VK had scuttled the plans of the Birla Group to manufacture Shaktiman trucks[6]. That was how HVF was set up in Avadi to manufacture these trucks and Vijayanta tanks. According to Nayar, about 60 MPs owed their allegiance to the Birlas. Morarji Desai, then Finance Minister, and MO Mathai, private secretary to Nehru, joined. According to him, this group campaigned against VK before and after the China War. According to Jaiam Ramesh, they also kept the Jeep scandal of the early 1950s alive, something Nehru had long forgotten.

Positions after retirement

In a sense, both did not actively pursue offices on their own. After Sardar Patel died in December 1950, the Ministry of States, of which VP was the only Secretary, was closed down the following April. In May, he was appointed Governor of Orissa, which he resigned two months later. He was then appointed a member of the first Finance Commission, which he also resigned a year later. He held no official positions after that.

VK’s primary career was as an activist in the UK, and Secretary to the India League before India became independent. This became infructuous with independence. He did suggest that he was best suited to becoming the first High Commissioner in the UK, given his long record and personal contacts. As he wrote in one of his letters to Nehru, “The British Government still appear to think that they can order us about…”. The need for a “strong High Commissioner who knew UK government, knew the way round … for a quarter century …” was repeatedly stressed. But, he left it to Nehru’s judgement.

In his second career as diplomat, VK went from the High Commission to head the Indian Mission at the UN, succeeding Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit. This was followed by a third career, as a politician and Minister, first as Minister without portfolio, and later as Defence Minister. He was bitter but did not bother to write his version of the events that led to his resignation.

After he resigned as Defence Minister, VK continued to be active politically, contesting elections, losing once and winning twice, the last as an independent from Trivandrum supported by the communists. He is perhaps the only Parliamentarian to win from three regions of the country. Neither Shastri nor Indira Gandhi considered Krishna Menon for any official position.

Honours

VP was bestowed with a Rao Bahadur by the British Government before independence. VK did not receive any such honour as these were usually reserved for those serving the government or its cause. After independence, VK was among the first Padma Vibhushan awardees in 1954. VP did not receive any such honour after independence.

Legacy

When the nation needs it, capable men and women arrive and make their mark. These two Menons were worthy examples of such visionaries. Both men have lasting legacies. In the case of VP, the sheer task of integrating 565 native states alone is sufficient to perpetuate his memory fittingly. However, adding to their differences, VP, despite his lack of formal education, faithfully recorded the most critical phase of life in three highly regarded books. On the other hand, VK Krishna Menon did not leave behind any book despite long years of education going into his late 30s.

PN Haksar[7] and MK Rasgotra[8], eminent civil servants, wrote how VK was fiercely dedicated to the nation’s cause. While independence was being fought for in India, what facilitated the process was the hard spade work done in the UK for shaping British public opinion towards granting India independence. This was an almost single-handed effort of VK Krishna Menon, for which his memory needs to be honoured appropriately. After that, his contributions in international diplomacy and as Defence Minister are unparalleled. VK has his statue and a road in Delhi named after him, which some bigots want to rename. VP has neither. VK also had two stamps issued in his name, one after his passing away and the other in his centenary year.

Menon vs. Menon

VK’s sphere of activity and what made him known worldwide were mainly outside India. VP’s work confined him to India, barring visiting London for the Round Table Conference. By the time VK returned to India for good in 1957, VP’s official career had ended a few years earlier. Still, there are suggestions that they disliked each other.

Contrary to what the two books suggest, there is no reason for animosity between the two Menons. The only time their paths crossed was during the few months before Independence when VK visited New Delhi after Mountbatten had taken charge. He engaged in hectic parleys as he had known Lady and Lord Mountbatten for years. Was he the subject of envy because the VP refers to him as a “busybody” in one of his notes? VP’s biographer also makes a passing reference to the “vaulting political ambition” of VK. This was, no doubt, uncalled for and not borne out by facts.

Notwithstanding the high position that VP reached, the fact remains that his sphere of activity was narrow, though very significant, and limited to a few years. VK’s canvas was broader: theosophist, publisher, freedom fighter, pacifist, diplomat, etc. Therefore, a comparison of their achievements would be odious. They stand tall for their reasons based on what destiny has offered them. Both the Menons deserve to be remembered and honoured more appropriately than they have been. Let us hope these two biographies are only a beginning.

The end

VP Menon settled in Bangalore after retirement and passed away on the last day of 1965. By then, his extended family had become bigger. Krishna Menon passed away on 5 October 1974 at his residence in New Delhi. He remained the loner that he was almost through his life.

The family of Romesh Bhandari, later Foreign Secretary, who had worked with Krishna Menon in the UK, was staying with him. PN Haksar, who met him during his last days, remembered that he was at peace with himself. Troubled but serene and without malice. But he could still make devastating comments about people. MKK Nayar, himself facing a motivated investigation (see here), called on Krishna Menon a few days before he died. He described Menon as sad and lonely. Krishna Menon held both hands and told him: “From the time of Ramayana, our country’s tradition has been to reject the most faithful.”[9]

Note:

Last revised on 4 October 2024

References

[1] Jairam Ramesh, A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V.K. Krishna Menon, Penguin Viking, 2019.

[2] Narayani Basu, V.P. Menon: The Unsung Architect of Modern India, Simon & Schuster India, 2020.

[3] Emil Lengyel, Krishna Menon, Walker and Company, 1962.

[4] TJS George, Krishna Menon: A Biography, Jonathan Cape, 1964.

[5] Emil Lengyel, ibid.

[6] MKK Nayar, With Malice Towards None: The Chronicle of an Era, Translated from Malayalam by Gopakumar M. Nair, Prism Books Pvt. Ltd., 2017.

[7] P.N. Haksar, “Krishna: As I Knew Him”, Broadcast on All India Radio, 6th October 1974.

[8] M.K. Rasgotra, A Life in Diplomacy, Penguin, 2019.

[9] MKK Nayar, ibid.

![]()