The year 2021-22 marks the sesquicentennial of Allama Abdullah Yusuf Ali. His remarkable life, caught between many worlds, was chaotic and turbulent, with its triumphs, tribulations, and a lasting legacy.

Contents

Introduction

In December 1953, six months after Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, London experienced another severe winter. Around the same time in the previous year, the city had suffered the Great Smog. Wednesday, the 9th, was freezing cold. Moving around was difficult. In the evening, in Trafalgar Square, Westminster, the police found an old man in tattered clothes, destitute and disoriented, on the steps of a house. He had a suitcase full of papers but no money in his pockets. They admitted him to the Westminster Hospital, which discharged him the next day. A London City Council home for the elderly, in nearby Dovehouse Street, Chelsea, took him in. The same day, he suffered a heart attack and was rushed to St Stephen’s Hospital. He died soon thereafter.

The man who thus passed into memory was Abdullah Yusuf Ali, formerly of the ‘heaven-born’ Indian Civil Service. Yusuf Ali is best known today for his monumental classic, an English translation, interpretation, and commentary on the Qur’an. It remains the most popular version of the holy book among English-speaking Muslims.

Yusuf Ali’s life from 1872 to 1953 can be told in two parts. The first, until around 1910, was a story of continuing rise and success on personal and official fronts. The second is the story of a slow, tragic, and tortuous descent, with moments of underappreciated glory and achievement.

Early days

Abdullah was born in Surat on 14 April 1872 as the second son of Yusuf Ali Allahbuksh, a police official. Yusuf Ali was a Shi’ite Ismaili in the Dawoodi Bohra tradition who converted to the Sunni sect. He also moved from the traditional trading business of the community to join the police. On his retirement, the government bestowed on him the title of Khan Bahadur. Abdullah seemed to be proud of his father’s title. Early official records show him as Abdullah bin Yusuf Ali, Khan Bahadur, bin meaning ‘son of’.

Education

After early religious education in Surat, Abdullah’s father shifted him to Bombay for better prospects. Abdullah joined the new Anjuman Himayat-ul-Islam, established by Badruddin Tyabji and other progressive Muslims to advance Muslim children. Tyabji later became the third President of the Indian National Congress. He also became the first Indian Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court. The Anjuman was the first school that combined Islamic and modern British education. Abdullah was among its first students. A few years his junior, for a brief period, was Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Abdullah learned enough of Islam and Arabic at school to memorise the Qur’an.

Abdullah later moved to Wilson School and Wilson College in Chowpatty, Mumbai, established by Rev. John Wilson, a Scottish missionary. He graduated in English literature in 1891 with a first class. He also earned proficiency in Latin and Greek History, winning prizes in both. These achievements earned him a Bombay University scholarship, which took him to St John’s College, Cambridge University, where he studied law.

Like many Indians studying in England during the period, Abdullah wrote the Indian Civil Service examination in 1894. (I learnt later that writing the ICS examination was a condition attached to the Tata scholarship, which was what probably took him to England.) His name came seventh on the list of successful candidates. After he joined the service in 1896, he was in absentia called to the Bar in Lincoln’s Inn. Later, while on a furlough in 1901, he added an MA and LLM to his qualifications.

Civil servant

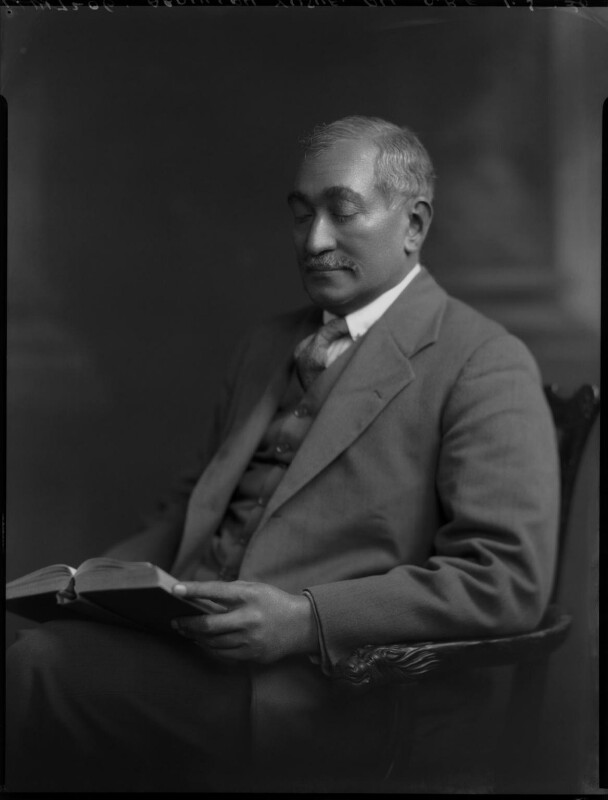

(licensed from NPG, London)

The government posted Yusuf Ali in the ICS to the North-Western Provinces and Oudh. In January 1896, his first posting was Assistant Magistrate and Collector in Saharanpur. He had influential British mentors, including Lord James Meston. As the Financial Secretary of the United Provinces, Meston spotted Yusuf Ali’s potential. Meston later became the Governor of the United Provinces. When he became the Finance Member of the Viceroy’s Council, he took Yusuf Ali into his department as Under Secretary and Deputy Secretary. Sir George Birdwood of the Bombay Medical Service, then at the India Office in London, was another British mentor.

Marriage

In 1900, during his first furlough, Yusuf Ali married Teresa Mary Shalders, a year younger. Unusually for an Indian Muslim, the marriage was consecrated at St Peter’s Church, in the Church of England tradition. One source suggests that Yusuf Ali concealed his marriage from his superiors. If true, this was probably to circumvent an old rule that mandated ICS officials to remain a bachelor until 30.

With Teresa, Yusuf Ali had three sons in 1901, 1902, and 1904 and a daughter in 1906. Like many civil servants of the Raj, he left his family behind in England while working in India. He made an appearance only when the rules allowed him a long furlough. On one such occasion, around 1905/06, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Prolific writer

On silk fabrics

Following another tradition in the civil service, Yusuf Ali also took to writing, which remained an almost lifelong pursuit. In 1900, Yusuf Ali published a monograph On Silk Fabrics Produced in the North West Province and Oudh. The book, which is still in print, covers well-researched technical details. The subheadings of the last chapter on “Silk in Folklore and Literature” reveal the depth of his scholarship. It covered popular notions of silk, superstitions about silk, silk in Sanskrit literature, silk in Hindu ceremonials, silk in Hindu festivals, silk in Muhammadan India, Moslem prohibition of silk as wearing apparel for men, and cocoon shells in Yunani medicine.

Life and labours of the people of India

In 1907, Yusuf Ali published his second book, Life and Labours of the People of India. He wrote it while on furlough after a successful tour in England. Lectures at the Passmore Edwards Institute and elsewhere formed the basis of the book written in the tradition of the 19th century English essayists… With striking attention to detail, it has chapters on village and town life, student life, civic life, and women’s life. It also covers the leisured classes, industrial and economic problems, and public health administration. The last chapter is on social tendencies. Embellished with epigraphs from major English poets, his anecdotes display a genuine academic curiosity about things around him. The book is a window to the young civil servant’s eclectic interests covering history, literature, architecture, and many other subjects.

Town life in Lucknow

Yusuf Ali chose Lucknow to describe town life. He etymologically traces Lucknow to Lakshman from the Ramayana. He also describes the finer architectural details of the Chatar Manzil. Describing the chowk, he says it will make one understand the meaning of the Latin expression, “Malum est! malum est!” inquit emptor; sed quum abierit tum gloriabitur! (Loose translation: It is bad, it is bad, said the buyer. But later, he gloats over the deal.)

He brought a deep knowledge of the land, its language, culture, and scriptures to his writing. This is how describes the churan seller:

“… he sells condiments and mixtures of digestive spices – sad commentary either on the quality of Lucknow cooks or the quantity which their patrons have time to eat but not stomach to digest. These little mixtures are carried in paper packets lying in two shallow baskets hanging from a pole slung over the man’s shoulder. This man is an artist in patter-song; he would stand up to your fastest singing artist from the most up-to-date music-hall. Fast come his words like pattering rain. In rollicking snatches of doggerel verse does he run over the virtues of half his churans before he once takes breath. But the excitement is greatest when two churan-sellers meet and try to talk each other down.”

Yusuf Ali, A. Life and Labour of the People of India, page 15.

Yusuf Ali also explains the nuances of chauk, bazaar, ganj, mandi, katra, tola, and mohalla, which refer to a market for different goods and services.

Promising future ahead

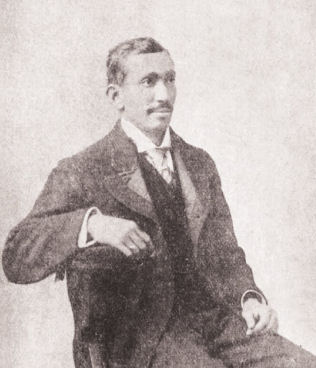

At this stage in life, Yusuf Ali could have looked forward to a successful career, retiring from the highest echelons of government. A photograph from these days shows a confident young man with a bright spark.

He could have been knighted and maybe become the Governor of a province or the Viceroy’s Council member. Further honours and decorations awaited him. His extraordinary abilities, supported by influential mentors, would have brought him wealth, positions, and recognition unimaginable to ordinary Indians. But fate deemed otherwise.

Divorce

Life was tough for many civil servants, especially the British, whose families were separated by continents. Yusuf Ali soon became one of them. After returning to India in 1907 following his furlough in England, he received news that Teresa was having an affair. It must have been in keeping with Edwardian mores. But it was difficult for a devout and humble Muslim from a middle-class Gujarati family to handle. It left him devastated, resulting in a nervous breakdown. He went on leave for about nine months through most of 1908. After Teresa had a child out of marriage in September 1910, Yusuf Ali had no option but to go to London to file for divorce. In 1912, he got a divorce and custody of his four children. He left the children with a governess before returning to India.

Resignation

Trouble soon came in one form or the other. In 1912, when he was posted to Kanpur, the municipality demolished a mosque’s ablution area and toilets to make way for a road. This resulted in riots. Left to defend the government, Yusuf Ali must have found dealing with his fellow Muslims a challenge. Some writers suggest that this was the real cause of his resignation from the service in February 1914. A few others cite the death of his children’s governess and the need to go back to England as the reason.

Yusuf Ali’s resignation was readily accepted. Despite his resignation from the service, Yusuf Ali maintained his friendship with Meston (later 1st Baron Meston) for another three decades till the latter’s death in October 1943. In the early 1940s, an aged Meston would write the foreword to one of Yusuf Ali’s last books.

The resignation in context

M.A. Sherif, Yusuf Ali’s only biographer (Searching for Solace, 1994), commented on the surprising ready acceptance of the resignation. He attributed it to the embarrassment that an Indian in the higher echelons of government would have caused many junior British officers. After nearly two decades in the service, Yusuf Ali had become sufficiently senior that it became impossible to avoid posting British officers under him. They were thus happy to see him leave.

But, there were perhaps deeper forces at play. Even if fellow civil servants had accepted him, there was a lack of acceptance from both English and Brown Sahibs alike. As Fielding-Hall wrote:

“An Indian who has entered the Civil Service is really in an impossible position. Socially he belongs to no world. He has left his own and cannot enter the other. And you cannot divorce social life from official life. They are not two things, but one.”

(Fielding-Hall, The Passing of Empire, 1913)

Fielding-Hall was writing about the tragic case of Pulicat Ratnavelu Chetty. In 1876, Chetty was among the first Indians and the first from Southern India to join the ICS. Posted to the Malabar district, he was not admitted to the white man’s club, where most important official matters were discussed and decided upon. Fellow civil servants were willing to admit him, but the other British gentry sternly opposed the idea. They threatened to blackball the application overwhelmingly. A frustrated Chetty shot himself in the head in 1881.

Opposition from the natives

Fielding-Hall states, “To put a native of one part of India over natives of another part of India would not please them; it would exasperate them. And even to put an official over his own people would not please those under him, though it might please his class.”

“The Government is English; a native official is not English. The people have no confidence in him for that reason. They know that he is not in intimate touch with Government. In the innumerable acts of official life which are not bound by rigid rules he is very likely to be wrong. When an English official says a thing they know he speaks with authority because his mind is one with that of Government; not so with a native official. They know it and he knows it, and he knows they know it. That makes matters difficult to begin with.”

“Moreover, they are jealous of him. When all high officials are English, natives are all together; put a native in as an official, and to the general native mind he is rather like a traitor. They have lost him and gained nothing. They are not proud of him but angry with him. He is as they are—why then should he have this power over them ? It is not a power delegated by themselves but by an alien Government. This is quite a simple fact in psychology and shows itself everywhere.”

Fielding-Hall, The Passing of Empire, 1913.

Yusuf Ali did not write his memoirs (Was there a draft in his papers?) It is only fair to him that we step into his shoes and imagine having undergone most of what is described above. But, in his case, life differed from that of Ratnavelu Chetty.

First World War

Yusuf Ali’s resignation coincided with the onset of the First World War. As the British were pitted against the Turkish Ottoman Empire, most educated Indian Muslims did not cooperate in the war effort. On the other hand, Yusuf Ali actively contributed with his writing, speeches, and lecture tours on the continent. On one such tour to Eastern Europe, he wrote, in 1916, Mestrovic and Serbian Sculpture. This short monograph of 32 pages reflects his scholarship in the Hellenic culture and affinity with a nation whose troubles had sparked the War. If anyone had been left in doubt as to where his loyalties lay, the book was “dedicated to the speedy success of the Allies and their intimate mutual understanding.”

After the War, the British honoured Yusuf Ali with a CBE for his efforts. He also accompanied the Secretary of State for India to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, representing India. These developments might have alienated him from mainstream Muslim thinking, including prominent Indian Muslims. This included Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, and Iqbal, the poet, apart from Muhammad Ali Jauhar, the founder of Jamia Milia Islami, Fazl Hussain, the Unionist, and Shaikh Abdul Qadir, the jurist. Like Yusuf Ali, they were influential and prominent in the community, all born in the 1870s.

Foray into education

Yusuf Ali always had an interest in education, having interacted at some point with Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan, the Islamic reformer, and Maria Montessori, the educator. He embarked on a career in education soon after the war ended. This involved teaching at the Notting Hill Islamic Centre and at the School of Oriental Studies, where he taught Hindustani.

Second marriage

Notwithstanding these engagements, Yusuf Ali must have felt a void in his life as his children slowly distanced themselves from him as they grew older. In 1920, Yusuf Ali married Gertrude Anne Mawbey, also an Englishwoman. Unlike his first wife, Gertrude converted to Islam. Yusuf Ali called her Masuma. But she liked to call herself Mrs Gertrude Ali. This marriage completed the process of alienation from the children from his first wife. They harassed his new wife, and one of them even verbally abused her. To protect her from this predicament, he relocated to India. In 1922, the couple had a son, Rashid.

Hyderabad and Lucknow

In India, Yusuf Ali joined the government of the Nizam of Hyderabad. From 1920, he worked in its Finance Department for two years. During this period, he also assisted in the working of Osmania University in its early years. He continued with his writing, now turning to more religious themes. He published a book on Urdu orthography and revised Wilson’s classic Anglo Mohammedan Law. In 1923, he published Muslim Educational Ideals, the first in a series of books on Islam.

From Hyderabad, Yusuf Ali moved to Lucknow, where he practised law and researched Mughal history and contemporary problems of the Muslims.

Life in Lahore

By the mid-1920s, Yusuf Ali was an intellectual with many published works. Muhammad Iqbal called him mubassar-i-zamana, a man with insight into the times. This was perhaps why, keeping aside other differences, Iqbal invited Yusuf Ali to head the Islamia College in Lahore. Yusuf Ali accepted it and remained Principal of the College from 1925 to 1927 and from 1935 to 1937.

In this phase, Yusuf Ali was a Fellow and member of the executive committee of the Senate of the University of Punjab (1925–8 and 1935–9). He was also a member of the Punjab University Enquiry Committee (1932–33) and on the Court of the University of Aligarh. He recognized secondary education as the weakest link and was active in various experiments in adult education. This included promoting the learning of vocational and craft-related skills.

Advice to students

As an educationist, this period saw him writing about Islam with increasing regularity. Perhaps reflecting his own approach to life, he advised his students moderation in all things. This was reflected in his writings, including in the commentary on the Qur’an:

‘In all things be moderate. Do not go the pace, and do not be stationary or slow… do not be talkative and do not be silent… do not be loud and do not be timid or half-hearted… do not be too confident and do not be cowed down.’

There was more such advice drawing from the Qu’ran:

‘We must not speak unseasonably and when we do speak we must not beat about the bush, but go straight to that which is right, in deed as well as in word’ and

‘Islam aims at making every Muslim man or woman, however humble in station, a refined gentleman or lady.’

He strove to inculcate certain values in his students in many ways. As he wrote to them,

“My dear, dear students! You are all dear to me, whether brilliant or stupid, dull or average, good or below the standard of goodness which I want and expect. In many ways, known and unknown to you, I have tried to shape your character and thoughts. Try to take a more cultivated intellect, a large heart, a fuller hope, a stronger will, and truer instincts as the legacies of your College life.”

Many alumni from his Islamic College days would later play significant roles in the early decades of Pakistan.

On denominational schools

Despite his interest in and writings on Islam, Yusuf Ali was against denominational schools. He wrote that

“denominational education if pushed too far tends to strengthen and perpetuate denominationalism in religion, that denominationalism flows into social life and tends to permeate it and that it embitters politics and hampers political progress.”

Yusuf Ali was, however, willing to consider it only as an experiment “on a limited scale can be tried without undue encroachment on the national edifice.” Speaking at the All India Muslim Conference in 1936, he argued for a broader education for Muslims, shedding formalism and stressing idealism instead of ‘special corners of isolation’. He warned, ‘Any community afraid to swim in midstream of its sister communities would find nothing but disappointment and disillusion in the final verdict of History.’

Allegations

In the 1937 elections, Yusuf Ali supported the Unionist Party, which defeated the Muslim League roundly. This alienated him further from Jinnah and Iqbal. Some people instigated various allegations against him at Islamia College.

The first was that he was not taking classes. He argued that he had no teaching commitment per the appointment’s terms. Nevertheless, he lectured at various forums. The second allegation was that he worked on translating the Qur’an during school hours. He clarified that this was not the case. The proofs were delivered to the College as it was convenient for the printer. The third was that his salary was quite high. Yet another allegation was his incompetence in Arabic.

Another resignation

In the face of such personal allegations, Yusuf Ali resigned in January 1937. This led to spontaneous and widespread protests and hooliganism by the students who asked him to stay on. He was touched by this spontaneous show of affection from the students.

His feelings for the young men of Lahore of those days are captured in these words, written around 1941 after he had separated from Masuma:

How can I ever forget you,

Dear young men of Lahore!

My dreams were entwined in your future;

Yours was my love evermore!Did you not lend me your heart-throbs?

Was not your happiness mine?

Shared we not, working and playing,

A joy like a breeze from the brine?When youth, in its freshness and glory,

Can be comrade to age that has faced

The chastening rod of experience,

Life yields of its most precious taste.Through books and through nature we wandered;

We laboured together, with zest;

Together we laughed when we captured

A truth that was wrapped in a jest.Then here’s to the days we look back to!

Truly a rich varied store!

Oh, how can I ever forget you,

Dear young men of Lahore!

Yusuf Ali valued his academic work so dearly that he earmarked a part of his estate to create a fund for Indian students at London University.

Other work in Lahore

Yusuf Ali was a private person who was selective about who he interacted with. This explains why only a few in Lahore knew about his earlier work. He was vice‑president of a Lahore association, ‘The Society for Promoting Scientific Knowledge’. On the cultural front, he was chairman of the Lahore Art Circle and a member of various clubs such as the Rotarians and the International Fellowship Society. Yusuf Ali founded the Lahore Art Circle and was its chairman in 1937. He was active in the World Congress of Faiths from 1936 to 1941 and participated in the Ethical Union, a similar body. He was also a member of the Lahore Rotary Club and spoke at the Round Table and Rotary Club meetings in Britain.

Religious work

Yusuf Ali’s involvement with religion intensified after he resigned from the ICS in 1914. After settling in Britain, he became a Trustee of the Shah Jehan Mosque in Woking, the oldest in the UK. In 1921, he became a Trustee of the fund to build the East London Mosque. He would later inaugurate and name the Rashid Mosque, Edmonton, the first mosque in Canada.

However, while in Lahore, he started writing increasingly about religion, especially for the Progressive Islam series. According to Sherif, “For Yusuf Ali, ‘progressive Islam’ was a catchphrase which did not harbour a burning iconoclasm but possessed a gentler focus, conveyed in the titles published in the ‘Progressive Islam’ series since 1925: Greatest Need of the Age; Islam as a World Force; The Fundamentals of Islam; Personality of Muhammad.” He also published in the series Moral Education: Aims and Methods (1930), Personality of Man in Islam (1931), and The Message of Islam (1940). The other books on the subject were The Religious Polity of Islam (1933). He also contributed to the Encyclopaedia of Islam. All these led to the Urdu Press calling him, like Iqbal, Allama, the most learned.

Translation of the Qur’an

Reasons

Translating the Qur’an was a natural step forward in Yusuf Ali’s spiritual journey. He probably did this with his students in mind. He might also have been inspired by Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall’s earlier translation, published in 1930 (The Meaning of the Glorious Koran). However, Yusuf Ali found this translation too literal.

It could also have been an act of penitence to reclaim his Islamic legacy late in life. This came after having espoused the cause of the Empire during the War, only to be packed off with an honorific and nothing else.

Whatever the reasons, it was another important landmark in his spiritual journey. For the first few years, he kept the project a secret until he revealed it to some of his students and friends in Lahore.

Circumstances

Yusuf Ali described in his preface to the translation the circumstances that led to the translation.

“A man’s life is subject to inner storms far more devastating than those in the physical world around him. In such a storm, in the bitter anguish of a personal sorrow which nearly unseated my reason and made life seem meaningless, a new hope was born out of a systematic pursuit of my long-cherished project. Watered by tears, my manuscript began to grow in depth and earnestness if not in bulk. I guarded it like a secret treasure. Wanderer that I am, I carried it about, thousands of miles, to all sorts of countries and among all sorts of people.”

In 1929, he travelled “through America, Hawaiian Islands, Japan, China, Philippines, Straits Settlements, Ceylon and India,” on his way back to India, working on his labour of love. In the 1930s, he immersed himself in translating the Quran. Though he did not speak Arabic, he knew the language, and his translation was widely acknowledged as a work of English literature. Initially published as pamphlets, it became a book in two volumes in 1938.

Motivations

The preface to the first edition describes Yusuf Ali’s motivations for writing the translation and interpretation:

“I have explored Western lands, Western manners, and the depths of Western thought and Western learning, to an extent which has rarely fallen to the lot of an Eastern mortal. But I have never lost touch with my Eastern heritage. Through all my successes and failures, I have learned to rely more and more upon the one true thing in all life — the voice that speaks in a tongue above that of mortal man. For me the embodiment of that voice has been in the noble words of the Arabic Qur’an, which I have tried to translate for myself and apply to my experience again and again.

“The service of the Qur’an has been the pride and the privilege of many Muslims. I felt that with such life experience as has fallen to my lot, my service to the Qur’an should be to present it in a fitting garb in English. That ambition I have cherished in my mind for more than forty years. I have collected books and materials for it. I have visited places, undertaken journeys, taken notes, sought the society of men, and tried to explore their thoughts and hearts, in order to equip myself for the task…

“Sometimes I have considered it too stupendous for me, — the double task of understanding the original, and reproducing its nobility, its beauty, its poetry, its grandeur, and its sweet practical reasonable application to everyday experience. Then I have blamed myself for lack of courage, — the spiritual courage of men who dared all in the Cause which was so dear to them.”

Style of translation

Sherif lists three factors affecting the style and content of Yusuf Ali’s magnum opus. The first was his setbacks in his personal life, leaving him “Searching for Solace,” the title of Sherif’s biography. The second was his academic training, teaching ancient Greek history after graduation, and abiding interest in Hellenic culture. Search for the “mysterious and unseen” in Hellenic thought influenced his approach to the commentary. The third was his experience as Principal of the Islamia College, Lahore, where he revealed his project to a few. They, in turn, urged him to publish it even if it were to be in instalments.

Approach to the translation

Yusuf Ali described his approach to the translation thus:

“The English shall be, not a mere substitution of one word for another, but the best expression I can give to the fullest meaning which I can understand from the Arabic Text. The rhythm, music, and exalted tone of the original should be reflected in the English Interpretation. It may be but a faint reflection, but such beauty and power as my pen can command shall be brought to its service. I want to make English itself an Islamic language, if such a person as I can do it. And I must give you all the accessory aid which I can. In rhythmic prose, or free verse (whichever you like to call it), I prepare the atmosphere for you in a running Commentary.”

“Introducing the subject generally, I come to the actual Süras — Where they are short, I give you one or two paragraphs of my rhythmic Commentary to prepare you for the text — “Where the Sura is long, I introduce the subject matter in short appropriate paragraphs of the Commentary from time to time, each indicating the particular verses to which it refers The paragraphs of the running Commentary are numbered consecutively, with some regard to the connection with the preceding and the following paragraphs İt is possible to read this running rhythmic Commentary by itself to get a general bird’s eye view of the contents of the Holy Book before you proceed to the study of the Book itself.”

Yusuf Ali added:

“Perhaps the attempt to catch something of that symphony in another language is impossible. Greatly daring, I have made that attempt. We do not blame an artist who tries to catch in his picture something of the glorious light of a spring landscape.”

Sample of interpretation

The success of Yusuf Ali’s translation perhaps lay in his bringing to it his prowess in writing poetry in English. Thus, he brought its intonation in recitation as close to the original in Arabic as possible. That is why Pickthall found his translation too free, while Yusuf Ali found the former’s translation too textual.

Illustratively, sample these three different versions:

Pickthall: “O mankind! worship your Lord, Who hath created you and those before you, so that ye may ward off (evil).”

Mohammed Shakir: “O men! Serve your Lord Who created you and those before you so that you may guard (against evil).”

Yusuf Ali: “O ye people! Adore your Guardian-Lord, who created you and those who came before you, that ye may have the chance to learn righteousness;”

On interpretation, Yusuf Ali also took an independent approach. Thus, on usury, he wrote that his “definition would include profiteering of all kinds, but exclude economic credit, the creature of modern banking and finance” (page 111, footnote 324). He thus tried to make his interpretation more in keeping with the times.

Comments on the translation

The end product was truly monumental. The 1946 edition was nearly 1900 pages long, with 6311 footnotes and many appendices. It received a mixed response. Mohammed Iqbal, known for long, made no mention of it. Pickthall was guarded in his praise: “It goes without saying that his translation of the Qur’an is in better English than any previous English translation by an Indian.” The sting in the tail did not go unnoticed. In private, he added that the translation was “too free”.

Pickthall was probably only returning the compliment. Yusuf Ali had written thus, concerning Pickthall’s translation: “He is an English Muslim, a literary man of standing, and an Arabic scholar. But he has added very few notes to elucidate the Text. His rendering is “almost literal”: it can hardly be expected that it can give an adequate idea of a Book which (in his own words) can be described as “that inimitable symphony the very sounds of which move men to tears and ecstasy.”

Sayyid Sulaiman Nadwi, the Pakistani Islamic scholar and historian, said, “The Muslim litterateurs have with unanimity spoken very highly of the beauty, eloquence and grandeur of [Yusuf Ali’s] translation.”

Translation over the years

Yusuf Ali’s translation went into several prints over the years, and its success overshadowed the author, who remains largely forgotten except as its author. His interpretation in the light of modern science appealed to the more educated younger generations. It gave the confidence that the religion would stand the challenge of the unrelenting march of science. Eventually, Yusuf Ali’s version would even become the basis on which unofficial and official efforts, often derided, were made to translate and interpret the Qur’an.

Yusuf Ali on Islam

According to Sherif, Yusuf Ali viewed “Islam as a comprehensive way of life”, with his commentary carrying the dominant theme of “a philosophy of other‑worldliness, significance of an ‘inner world’ and pursuit of moral excellence.” He was “far more in his element presenting the message of the Qur’an as a message of individual hope rather than a source of guidance for the governance and management of society. Piety was personal worship rather than seeking to apply the spirit of Islam to address sociopolitical issues.”

Notwithstanding his deep involvement with Islam, Yusuf Ali remained interested in other cultures, other faiths, and interfaith dialogue, as seen from his active involvement with the World Congress of Faiths.

On politics and Islam

Early in his career, partly because of his career in the ICS, Yusuf Ali turned his back on ‘political Islam’ or ‘controversial politics’, which meant having to take on his masters. He felt that such an approach detracted from the ability to tackle the real issues facing the country. During his Lahore days in the late 1930s, Yusuf Ali was indirectly involved in two elections. He supported the Unionists on both occasions. His bitter experience on both occasions reinforced his belief in the need to separate politics from Islam.

Yusuf Ali abjured political Islam as for him, the only form of collective action based on religion was to be a spiritual fellowship. In Religious Polity of Islam, he wrote that it was ‘too narrow bounds to Islam to identify it with any particular set of concrete customs or institutions, however wise and reasonable they may have been in origin’.

Sherif lists three reasons for this approach. First, he felt politics had become “demeaning for pious and religious men.” Attacking Indian Wahhabism in 1906, he had warned against ‘the thoughtless admission of the foul and tainted exhalations of rough‑and‑tumble politics to what should be the pure and serene atmosphere of religious peace and freedom’. Secondly, he believed a true Muslim should obey the day’s ruler for order and discipline. The third reason was his belief in the inevitable evolution of societies that would shape history in a manner unknown to ordinary mortals.

Cultural history of India

Yusuf Ali supported the League of Nations, believing that it might be a forum to ‘further the progress of mankind’, and also participated in its ‘Peace through Religion’ programme.” He served on the Indian delegation to the League of Nations Assembly in 1928. In September 1931, in the context of the Second Round Table Conference, where separate electoral colleges for Muslims were one of the raging debates, Yusuf Ali completed his work on Hindustan ki Tamaddun ki Tarikh (A Cultural History of India). He wrote in the book that “culture must assimilate culture or human evolution would be stopped forever.”

Cultural History was a counter to those who wanted greater independence. In particular, it countered Iqbal’s Allahabad 1930 resolution calling for a separate Muslim State. He said that British thinking underlay the call for such independence: ‘The evolution of British Indian culture is dominated by British ideas, which lurk even beneath the protests of those who are in revolt against what they term foreign ideas.’ But, in literary meetings, he would recite Iqbal’s poetry and compare him to Claudel and Nietzsche, “revitalising his people”, especially the latter.

Separate Muslim state

In December 1932, Yusuf Ali became President of the All‑India Muslim Conference (AIMC), held in Calcutta. The AIMC was set up by Fazli Hussain in 1928 to undermine the Muslim League and its president, Jinnah. Previous presidents of the AIMC were the Aga Khan, Shaukat Ali, Jauhar, and Iqbal.

Yusuf Ali differed from the views of Jinnah, Iqbal and others that Muslims required separate political treatment. His views transcended denominational politics. He dismissed the idea of Pakistan as a student’s scheme. He foresaw that mutually exclusive zones for Hindus and Muslims were not practicable as it involved an impossible exchange of populations. But, his proposals for a composite party had no takers. Thereafter, he seemed to have gone with the views of other Muslims but was not happy with Partition as it happened.

Yusuf Ali and other Indians

In his writings, Yusuf Ali largely ignores contemporary Indian sources. An example is his Making of India, published in 1925, where he still refers to the uprising of 1857 as the Great Mutiny. In contrast, almost two decades earlier, V.D. Savarkar had termed it the first war of Indian independence in an eponymous book. In over 70 references in the same book, there are only five by Indian authors: Romesh Dutt on Indian economic history, Ameer Ali on the Life of the Prophet, S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar for Kingdoms of South India, Tagore on nationalism, and Beni Prasad on Jahangir. An answer to this lies in the Britishness he sought to acquire early on.

Yusuf Ali and the Empire

Sherif wrote that Yusuf Ali “acquired a Britishness that was untypical.” According to Khizar Ansari, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, “Yusuf Ali belonged to the group of Indian Muslims from professional families concerned with rank and status. In pursuit of his aspiration for influence, deference, if not outright obsequiousness, became a central feature of his relationship with the British. During the formative phase of his life, he mingled mainly in upper-class circles, assiduously cultivating relations with members of the English élite. He was particularly impressed by the genteel behaviour and cordiality of those with whom he associated, and, as a result, became an incorrigible Anglophile.”

According to this narrative, “His marriage to Teresa Shalders according to the rites of the Church of England, his hosting of receptions for the good and the great, his taste for Hellenic artefacts and culture and fascination for its heroes, his admiration for freemasonry in India as a way of bridging the racial and social divide, and his advocacy of the dissemination of rationalist and modernist thought through secular education were all genuine attempts to assimilate into British society.”

Sherif also suggests that Yusuf Ali’s appeasement of Britain during the War against the Turkish Empire and support for the Unionists were “exaggerated patriotic gestures … an attempt to redeem himself in [his family’s] eyes.” But, he adds, “There could also have been other subtler factors at work. The King was the distant, kindly father commanding obedience from his children, loyal subjects of the Empire. It may be that Yusuf Ali craved for the same filial adoration from Alban (his son) and his siblings which he himself offered to George V.”

Making of India

An extension of his appeasement of British India was his glossing over unpleasant events. Thus Yusuf Ali in his Making of India (1925) understates the importance of incidents such as the Jallianwala Bagh and the Moplah Riots a few years earlier. A reviewer for the Times Literary Supplement wrote that he ‘touches lightly on what he calls atrocities and unedifying facts.’ But, he conceded that “The Mopla rebellion of August 1921 shattered the hopes of either a non-violent co-operation or of Hindu-Muslim unity.”

Second separation

Perhaps in the 1930s, with his greater involvement with religious writings and longer stays in India, Yusuf Ali’s second marriage failed. For most of the 1920s and 1930s, after his children from the first marriage had left him, he stayed at the National Liberal Club whenever he visited London. Later, he moved to No 3, Mansel Road, Wimbledon, his house, which he had transferred to Masuma in 1933. He continued to stay there after the War ended in 1945, even though Masuma had moved out. She sold the house in 1948, and Yusuf Ali moved to a rundown area of London.

Independence and partition

According to one source, Yusuf Ali returned to India after independence, like many others. Many of them got some political posting or the other. But Yusuf Ali was not one of the lucky ones. He did not seem wanted in either India or Pakistan. He was, after all, around 75 years of age by then. Incidentally, he had once crossed swords with V.K. Krishna Menon, Nehru’s intellectual confidante, in a public debate in England. Moreover, he had not kept in touch much with the national leaders in either of the two new nations.

The Unionists with whom he had associated joined the Muslim League in Pakistan. He did not also figure in Jinnah’s scheme of things. Old slights would have rankled. Not getting recognition, Yusuf Ali returned to England disappointed, disheartened, and disillusioned.

The lonely soul

Without any position to keep him busy, estranged from family, ignored by the British government, which found no use in him, unwanted by the two newly independent nations, and his friends and mentors long gone, only an odd official of the Pakistan High Commission was in touch with Yusuf Ali—that too rarely. His mind and health slowly deteriorated. With his last house sold, he lodged mostly at the National Liberal Club or the Royal Commonwealth Society.

In 1951, Omar Abdullah, a young scholar from Comoros, met Yusuf Ali at the Royal Empire Society. When he asked the staff for Yusuf Ali, they asked whether he was looking for that old man sitting alone, doing nothing and talking to no one. On meeting him, Omar asked him about the translation. Yusuf Ali said it took him three years and that he wrote it in all continents. He added that he visited every place mentioned in the Qur’an.

Changing the subject, Omar observed that Lahore was an ideal place for a Muslim. Yusuf Ali replied, “But it is no longer… And I’m quite happy here, I’m satisfied.” Omar’s lasting impression was of a man who had reached the highest spiritual level. Did he wilfully choose to live in poverty, wandering in the streets of London despite having over 20,000 pounds in the bank?

The last day

Soon after being admitted to the hospital, he might have given the name of someone at the Pakistan High Commission. Or it is possible that someone at the hospital guessed his nationality or found some identification document or a piece of paper on his body that led them to the Pakistan High Commission. It was they who claimed his body and paid for his last rites. The inquest proclaimed ‘senile myocardial degeneration’ as the cause of death. He was buried in the Muslim section of Brookwood Cemetery in Woking, Surrey.

Inheritance

In 1940, already in his 60s and the Second World War had started, Yusuf Ali wrote his will. He had transferred ownership of 3 Mansel Road to Masuma in 1933. She sold this in 1948. His will left hardly anything for his children, including Rashid, saying, “These children by their continued ill‑will towards me have alienated my affection for them, so much so that I confer no benefit on them by this my will.” He was particularly harsh on the second son, Asghar, who “has gone so far as to abuse, insult, vilify and persecute me from time to time.” Most of his estate went to create a fund at the University of London for Indian students at the University.

Rashid was to get a lump sum of 4,000 and 40 pounds every quarter for life. Yusuf Ali might not have known that, in 1944, Rashid had joined the 7th Rajput Regiment of the Indian Army. For Masuma, he left 40 pounds every quarter until she remarried, apart from furnishings, his writings, papers, and books. The remaining books were to go to Islamia College, Lahore. A prolific writer, Yusuf Ali was also a voracious reader. By 1930, Yusuf Ali’s collection of books at Mansel Road was so large that he insured his library separately for £500. He bequeathed his diaries to the Aligarh Muslim University, to be opened 30 years after his death.

Masuma and Yusuf Ali had separated in 1941. Yusuf Ali’s pension of 800 pounds until his death left over 20,000 pounds in the bank, which must have gone to Masuma, along with the books and papers. What happened to the books and diaries was a secret that she carried to her grave in 1962.

Legacy and assessment

Yusuf Ali was one of the first non-Bengalis and Muslims, and perhaps the first from Gujarat, to have joined the Indian Civil Service (ICS), the steel frame of the British Indian administration. But, in a note on Indian members of the ICS in the nineteenth century, the proceedings of the Indian History Congress (Volume 30, 1968) explicitly removed the names of Yusuf Ali and five others from its analysis as they could not trace their names in the ICS civil lists for the period.

Yusuf Ali was a bright and talented man with eclectic interests. With the best of education in late-Victorian India and England, he was employed in the most prestigious service of the Crown that an Indian of his background could aspire to. He was moulded by the Edwardian values of the first decade of the 20th century, and he looked forward to greater prosperity backed by technology for the Empire and the world. After welcoming a 20th century full of hope, the beloved of his bosses, he had his sights on the highest echelons in his service. A knighthood and other honours awaited him. But, as we have seen, his was a story of events that made him turn inward as the years progressed.

A Wikipedia page on Indian Civil Service officers includes Surendranath Banerjea and Subhas Chandra Bose. The first was dismissed, perhaps wrongly, not long after joining the service. The second resigned soon after being selected. However, Abdullah Yusuf Ali, who served the country for nearly two decades, did not appear until this author had the honour of adding it.

Assessment

Yusuf Ali lived across many worlds. Torn between tradition and modernism, the scriptures and modern science, an aspiring India and a defensive Britain, Indian customs and values, and British manners and etiquette, at once the ruler and the subject, Yusuf Ali, tried to bridge the gap in his unique ways. Translating the Qur’an into English was one such attempt. After partition, he was perhaps unable to choose between a secular India, where he was born, and a Muslim Pakistan that did not want him.

According to Sherif, Yusuf Ali became a model for many Pakistani bureaucrats to be Europeanised while maintaining roots in Islam. He quotes the edict of Piyadasi, another name for Emperor Ashoka, to say, “The most worthy pursuit is the prosperity of the whole world.”

As Sherif wrote, “A type of Muslim personality emerged in the colonial period that saw its main goal to be the creation of a synthesis that would, in some mystical union, reconcile the rulers and the ruled. Yusuf Ali was driven by a deep‑seated psychological urge to build a bridge between East and West.”

Yusuf Ali’s Passmore lectures in London in 1906 were the first time he spoke about his quest for harmony between East and West. He saw himself as one of those ‘University men in India’, referring to the Oxbridge-returned graduates ‘whose minds are still seeking an adjustment between Western ideals and Eastern traditions’.

In 1937, he warned a Muslim audience at Aligarh, ‘It would be a mistake on the part of the Muslim community to slacken in their study of English, which is the administrative language of India now and will remain so for as long as we can at present foresee.’

The future

Yusuf Ali held out hopes for a better future for the entire world. As he wrote in one of his poems:

If East and West thou couldst survey,

And North and South in Art unite,

‑Why is the human spirit’s sway

Less potent now, why dimmed its light?

Have faith: these birth‑throes but presage

For all humanity a Great New Age!

Whatever might have been the shape of the New Age he wanted, it would not come in his lifetime. As the obituary in The Times, London observed: ‘In advancing age, he seemed to have a sense of frustration to find that so much of what he had done was vanity and vexation of spirit… He wandered about at the end, an unquiet spirit with no fixed abode.’

References

This biographical sketch relied on the following:

“Searching for Solace: A Biography of Abdullah Yusuf Ali, Interpreter of the Qur’an” by M.A. Sherif;

Yusuf Ali memorial oration by M.A. Sherif;

Peter Clark on Yusuf Ali for the Encyclopaedia of Islam;

Khizar Ansari on Yusuf Ali for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; and

Numerous works of Abdullah Yusuf Ali, including his translation, interpretation, and commentary on the Qur’an.

Note

This post was revised on 30 May 2024 to add a list of contents and to correct certain typological errors.

![]()