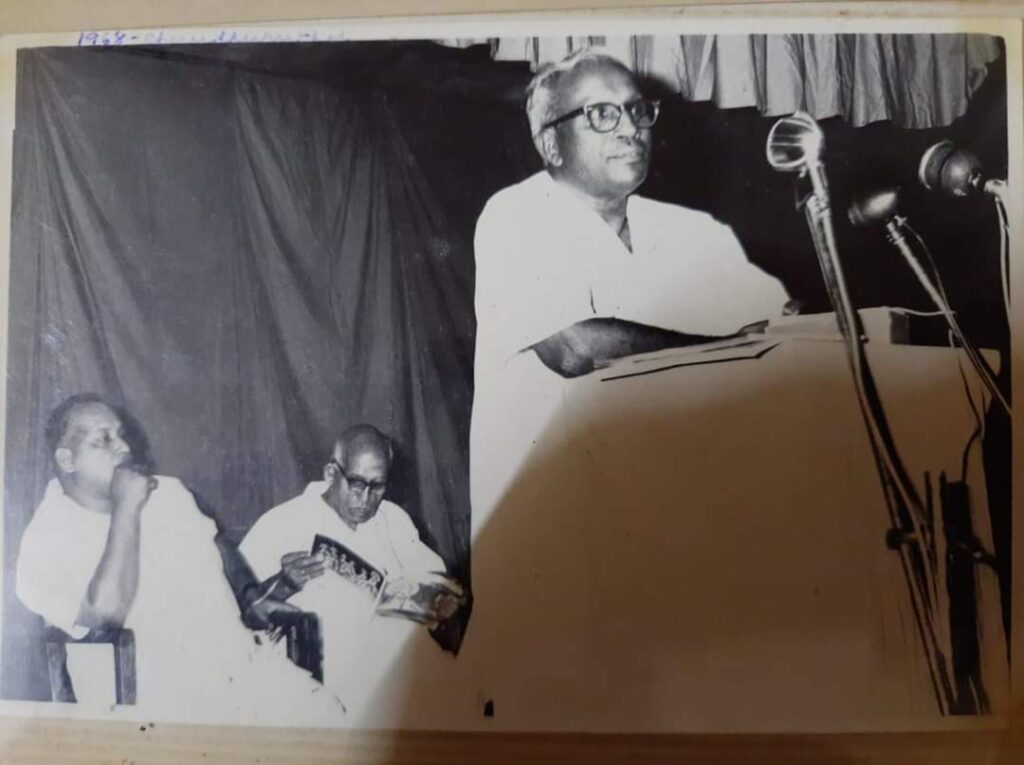

This is a centenary remembrance of the Late MKK Nayar (1920-1987), my father’s boss, who belonged to the first batch of IAS. Though belonging to the Tamil Nadu cadre, his significant contributions include the construction of the Bhilai Steel Plant, modernising FACT fertilizer plants, and the world of sports, arts, and culture in Kerala and beyond.

Introduction

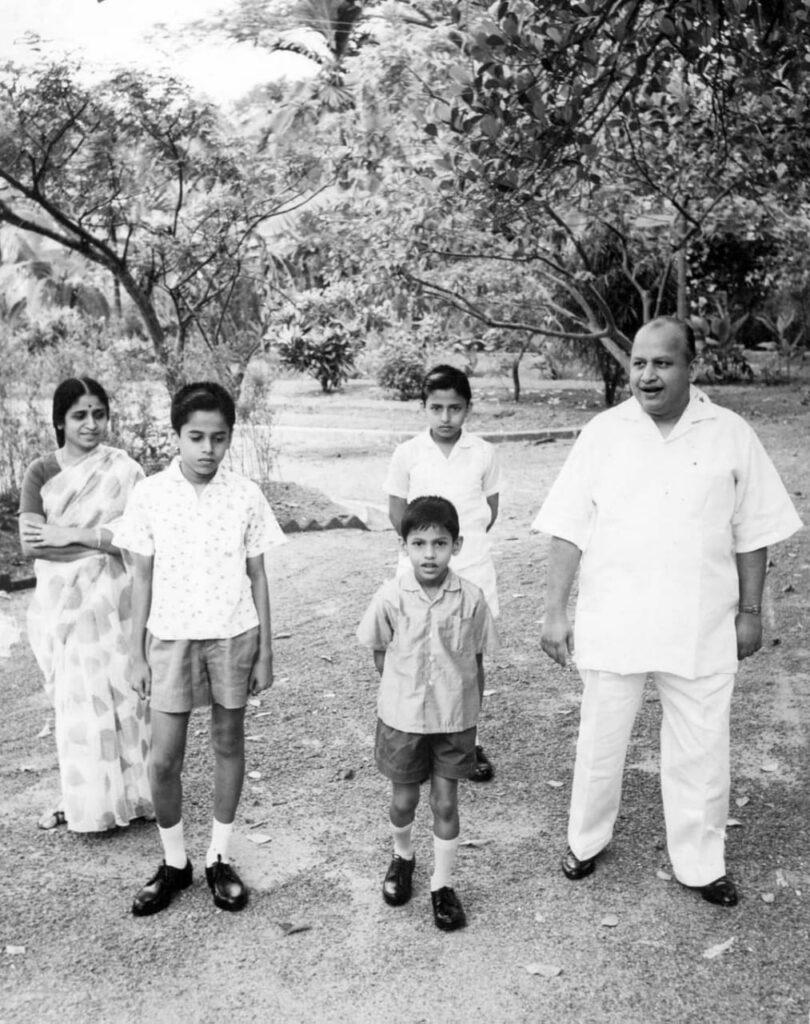

Sometime in mid-1966, I was five, sitting with my dad, mom, and brothers in a living room, waiting for someone. My mom suddenly asked me and my brother to show how MD Uncle laughs. My brother jumped off the sofa, pushed his tummy forward, and laughed loudly – ahahaha! Looking on and tilting his head in camouflaged amusement was Pappu, the serious-looking white fluffy Pomeranian. He was the first toilet-trained pet that I ever saw.

Not to be left behind, I also slid down the sofa, pushed my belly further outward, and cried out louder and longer – ahahahahaha! As I was completing, my laugh echoed from inside. Soon emerged a plump man of medium height, sporting a large paunch, clad in a well-stitched and meticulously ironed white khadi shirt and pants. With a strikingly auspicious bald head and a genial face, you will not easily forget him if you have seen him once. A second time, and you may be forever drawn into his indescribably magnetic aura. Such was his personality. That was Meppally Keshava Pillai Krishnankutty Nayar. MKK Nayar, as per official records. Krishnankutty to elder relatives, others suffixing it with chettan, or elder brother. MKK to friends. To us four brothers, he was always, then as now, MD Uncle. MD referred to his tenure as the Managing Director of FACT.

MKK and my father

First meeting

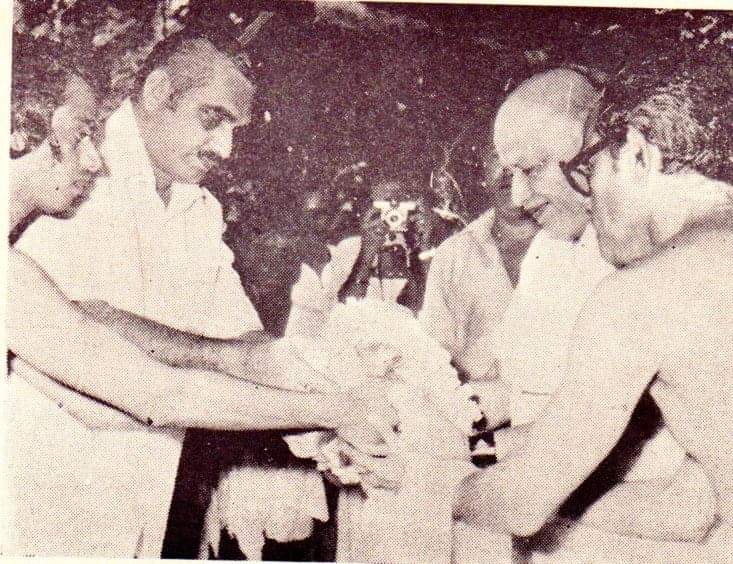

My father, N Gopalakrishnan Nair, met MKK sometime in 1959 when he was then the sub-collector at Palghat (now Palakkad). MKK had come to address an event that my father had organized. MKK had then recently taken charge as Managing Director at Fertilizers and Chemicals Travancore Ltd (FACT). FACT was established in 1943 as India’s first fertilizer company, among the many institutions that owe their existence to the vision of Sir C.P. Ramaswamy Iyer, Dewan of Travancore, from 1936 to 1947.

MKK must have liked my father’s speech enough to ask one of the other speakers, MP Manmathan, the famous Gandhian and social worker, about my father. Manmathan must have given a good report. My father started his career at 19 as a lecturer at the NSS College, Pandalam, where Manmathan was the Principal. A year later, he moved to University College, Trivandrum, from where he had graduated. He taught there for five years before joining the IAS in 1957.

Fertilizers and Chemicals Travancore

Two years after that brief encounter, and a month after I was born in July 1961, my father was posted as Chief Commercial Manager, FACT. MKK described the first official meeting as follows:

“When I first saw this young man in chocolate colored corduroy long trousers and bush shirt, I had not been impressed. But after talking with him for half an hour, I was able to gauge his wide mental reach, far sightedness and determination. I saw that he was imaginative, could judge situations quickly and take firm decisions like ICS officers of a gone-by era.”

MKK Nayar, “With Grudge Against None”

In his memoirs, MKK credited my father with starting FACT’s Executive Development Programme and Fertilizer Festivals. In 1964, my father moved to the then-undivided Cannanore district (which included the present Kannur and Kasargod districts) as District Collector. He returned to FACT in June 1966 at the invitation of MKK to set up its Cochin Division in Ambalamedu. The factory and township were completed in less than five years. One of the highlights was an artificial lake with an island hosting Charles Correa-designed Ambalamedu House, retaining the original natural beauty of the landscape to the extent possible.

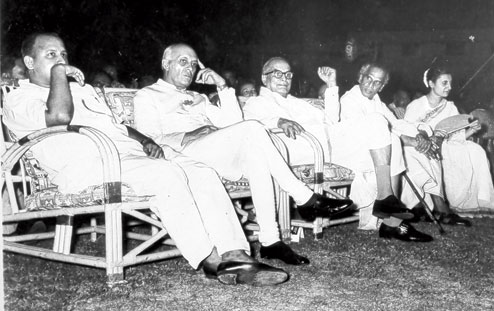

The anecdote discussed at the beginning occurred during our first visit to the Managing Director’s residence after returning to FACT. Since then, I have seen MKK in numerous places: FACT’s Udyogamandal Club, official dinners at our house in Ambalamedu, his Ernakulam and Trivandrum homes, our house in Trivandrum, innumerable weddings, concerts, Kathakali programmes, including the three-day annual event at his ancestral home Meppally, literary gatherings, temples, including Sabarimala, and so on. Everywhere, MKK’s was always a profound presence felt across any event or occasion.

MKK at FACT

Half a century has elapsed since MKK stepped down from FACT, where he was MD for the first ten years. All others who came later were CMDs. Nevertheless, even five decades later, only one name appears whenever FACT is mentioned. Everyone enquires about only one person: MKK Nayar.

With the second five-year plan, the role of fertilizers was recognized for a growing economy. That was when the Central Government took over FACT from the Seshasayee Group. To actualise a vision of converting a company with a turnover of Rs 50 lakh to one with a turnover of around Rs. 600 crore, the government needed the services of a very competent officer. They did not have to look far. MKK Nayar, who was put in charge of commissioning the Bhilai Steel Plant with Russian collaboration and had completed the work in 18 months, then a world record for such plants, was appointed Managing Director in 1959.

Cochin Division, Ambalamedu

As part of the expansion programme of FACT, a new Cochin Division to be set up at Ambalamedu was envisaged. For this project, he was looking for a suitable officer from the Indian Administrative Service to be brought on deputation from the Kerala State cadre. That was when he came across my father’s confidential report, in which a Revenue Board member had recorded that he always delegated his work. What was intended to be a negative observation was interpreted in a positive sense by MKK, who felt that upscaling a company severalfold required an officer who could delegate and take people with him. This instance sheds light on MKK’s distinct style of thinking.

My father was happy to have a second chance to work with MKK. Since it was equivalent to a Central Government deputation, that too a second one, it helped him delay an inevitable posting in New Delhi, at least for some time. Eventually, he never went to New Delhi. That was how my father returned to FACT for a second stint in 1966.

My father eventually dedicated his book on Management (Management – Kalayum Shastravum), written in Malayalam, to MKK Nayar, describing him as his guru in Management. The book, first serialised in 1971 in Mathrubhumi Weekly and edited by M.T. Vasudevan Nair, later a Jnanpith Award winner, had an excellent foreword written by MKK.

MKK Nayar and CBI

A frivolous case

After 12 years at the helm of FACT, handling billions of rupees and elevating its stature to a global level, MKK was haunted for over a decade after leaving FACT by two CBI cases: one regarding misuse of official position and the other regarding assets disproportionate to known sources of income. These cases, after passing through the touchstone of judicial scrutiny, involved a paltry amount of Rs. 3,000. Several parallel and unrelated developments contrived to result in the CBI filing an FIR against MKK.

A disgruntled civil servant

The first was a Specially Recruited (only interview, no examination) civil servant who had a complex with regularly recruited officers who came through the examination route. He had approached MKK for a secondment to FACT but was refused. He later became a GM and MD at Travancore Cochin Chemicals, also in Udyogamandal.

This officer was KV Ramakrishnan, better known as Malayattoor Ramakrishnan, who prided himself on being a litterateur, artist, and cartoonist. But, to his dismay, he found that in the world of art and culture, apart from official management-related functions, MKK held sway. Whether it was the setting up of the School of Management under Dr MV Pylee, running of the Kerala Management Association, establishing a Lalit Kala Akademi, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, or a Bala Bhavan, or improving the functioning of Kerala Kala Mandalam and a host of other institutions, MKK was the lead catalyst or initiator of change, like a lead tusker in a temple festival.

The origin of allegations against MKK is believed to be this officer’s office, in whose guest house FV Arul, then Director of the Central Bureau of Investigation, stayed. This officer’s explanations in his autobiography lack credibility. His shallow and high-handed approach to art and culture was lampooned in the movie Celluloid, which dealt with the life of JC Daniel, the father of Malayalam cinema.

The CBI initiated a routine investigation based on complaints. MKK’s house and offices were raided. They obtained MKK’s diary, where he had recorded his free and frank views on various matters. This included comments critical of the then Prime Minister. The same officer is believed to have ensured, through Arul, that these observations were brought to the PM’s notice.

A disgruntled parliamentarian

The second was one Arangil Sreedharan, who then represented the constituency of Vadakara, Kerala, in the Lok Sabha. He wanted a few candidates selected as Management Trainees at FACT. As that followed a transparent system of examination and interview, MKK pleaded his inability to interfere. A slew of parliament questions and a signature campaign against MKK by some Kerala MPs, orchestrated by Sreedharan, followed. Most leading Kerala MPs, like AK Gopalan and N Sreekantan Nair, were either not approached or rebuked those behind the campaign.

A defaming publication

The third was the editor of a magazine, who wanted an advertisement from FACT every week. This was also refused. What was promised were two advertisements on two national days. This was the approach towards similar journals, including Shankar’s Weekly, whose editor Shankar, the cartoonist, was a long-time friend of MKK Nayar. This editor instigated a scurrilous article, The Snake in Fertilizers, published in Mainstream, a publication then edited by Nikhil Chakravorty. A defamation suit filed by MKK unnerved Chakravorty, who published an apology as demanded by MKK. Nevertheless, MKK’s detractors used the article to initiate another investigation. PR Nayak, ICS, who conducted the investigation, exonerated MKK.

Advice to collect political funds

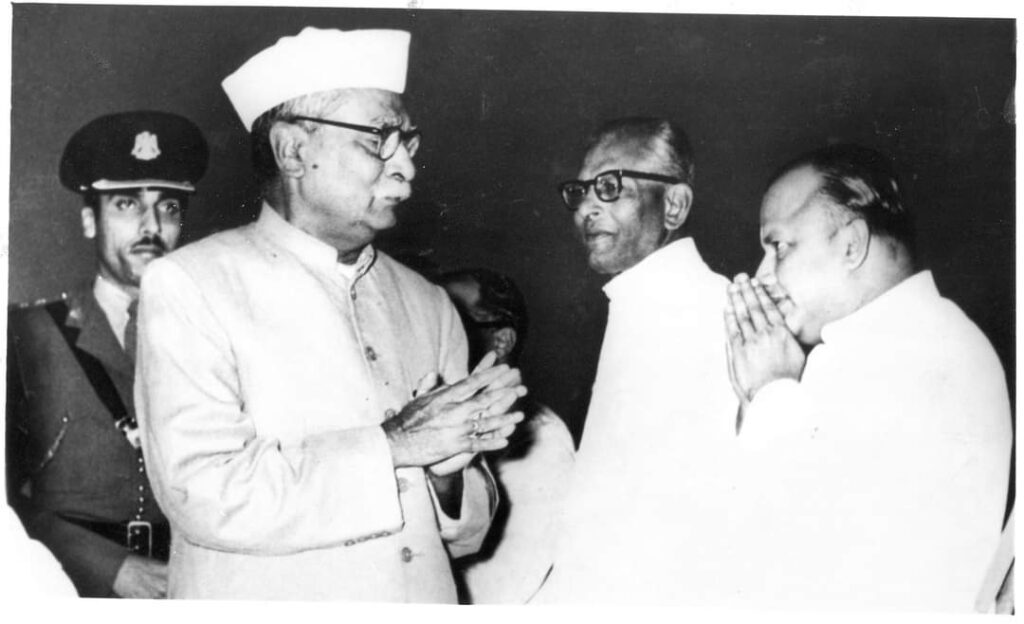

The fourth was a Minister of State who approached MKK, asking him to raise Rs. 60 lakh for party funds from suppliers and other counterparties. MKK replied that he was unfamiliar with that kind of work and that the minister need not expect anything from him. As luck would have it, after the next general elections in 1971, this leader became Cabinet Minister in charge of Petroleum and Chemicals. In the next shuffle of officers under the Ministry, MKK was transferred to the Planning Commission as Joint Secretary.

The Prime Minister sought the views of C Subramaniam in the matter of allegations against MKK. Subramaniam, then Vice Chairman of the Planning Commission, where MKK had moved in 1971, recorded:

I know this officer very well from 1951. He is the most capable and pure-minded civil servant in India now. It is my belief that no allegation levelled against him will stand. Therefore, a decision may be taken on this only after proper consideration.

Permission was not given to the CBI to proceed with the case.

The final push

The final push came in the form of a case against an officer from a backward community. As the government had not allowed the case to be dropped, the withdrawal of the case against MKK was cited as a precedent and an instance of favouring an officer from a forward community. C. Subramaniam had moved on from the Planning Commission, and D.P. Dhar took his place. This finally led to the filing of an FIR against MKK.

MKK’s memoirs show that some of the officers in CBI, especially the then Director Arul, also from the same Tamil Nadu cadre as MKK, took a personal interest in pursuing the case. Arul also got one of his “trusted sidekicks”, PV Narayanaswamy, promoted and transferred from Tamil Nadu to Kochi to be in full charge of the case.

The case thus had a small beginning, born out of jealousy and compounded by other parallel developments. It was then within MKK’s ability to have the proceedings quashed, but he chose not to influence anyone to nip the problem in the bud.

Two Judgements

In both the cases of misuse of official position and disproportionate assets, CBI took almost ten years to complete its arguments. The objective was to ensure that MKK, who was to retire in 1978, should never come back in service. In her 1983 judgment in the disproportionate assets case, Justice Elizabeth Matthew Idiculla sharply criticized the CBI in the following words:

“The disproportion of assets which has been pictured as gigantic in the charge and which lost nearly half its size when dealt with by the Public Prosecutor is proved to be too tiny when tested by the touchstone of judicial scrutiny. This combined with the additional facts that the trial of this case has been unduly delayed due to the reasons already detailed by me in the initial portion of this judgement which must be deemed to have caused serious prejudice and harassment to the accused for which he is not in any way responsible and also that the investigating agency stooped to concoct Ext P 467 (false document of authorization) which is not expected of any investigating agency much less a solemn body like the CBI deter me to enter a finding of guilty against the accused… In the result, I exonerate the accused …”

Quoted in MKK Nayar, “With Grudge Against None”

Justice VK Bhaskaran, in his judgement in the second case, commented on the CBI’s FIR as follows:

“In the final analysis of the case it will be seen that a false FIR containing wild allegations against the accused was filed in court on 31 May1969. But the Investigating Officer did not submit any report to the court in respect of the allegations contained in the charge sheet before filing the charge sheet. During the investigation, the Investigating Agency appears to have adopted dubious devises like creating false evidence and suppressing material evidence in order to see that by hook or crook, the accused is convicted of some offense. It is unfortunate that a machinery such as CBI which is a powerful investigating agency and supposed to be highly efficient had resorted to such practices in vital matters involving the prestige of the citizens. It seems, the accused with equanimity has undergone a great ordeal by facing the trial protracting for a period of more than ten years. But for this accusation he should have held some of the highest positions of responsibility in our country to the benefit of the people.”

Quoted in MKK Nayar, “With Grudge Against None”

The two cases showed us how, in our system, jealous and despicable enemies in powerful positions, small men as they are, can bring down even a popular and competent official who should have retired as Cabinet Secretary in the ordinary course. The comments against the CBI by the two honourable judges were never contested and remain a lasting indictment of the organization. MKK Nayar, on his part, chose to leave the CBI officials to the mercy of God rather than have them prosecuted under the Indian Penal Code for creating false documents and using them with the full knowledge of their being false, an offence punishable with seven years’ rigorous imprisonment.

Other Issues

Denial of benefits

Even after the case was won, MKK’s enemies succeeded in denying him the benefits he was entitled to with retrospective effect. It is poetic justice or divine retribution that the junior Minister in the then Rajiv Gandhi cabinet responsible for denying MKK his due benefits and his son recently spent long periods in Tihar jail for forgery, corruption, cheating, money laundering, and disproportionate assets.

The case never demoralised the strong man that MKK was. Even at the height of the proceedings, whenever I met him at his residence in Ernakulam, I found a pleasant human being who always enquired about my studies and the books I read. More serious was Pappu still strutting about with his quiet, graceful steps, in apparent disgust of the goings-on around him.

A car accident

An almost fatal car accident followed around this time, resulting in several months of stay in hospital and an eye surgery. MKK lost 32 kilos in six weeks. Even this did not unsettle him or wipe off that ever-present genial smile from his face.

A mark list case

Then came a mark list case involving his second son. This resulted from the machinations of a doctor brought to prominence by MKK himself. Several public sector undertakings in and around Cochin (now Kochi) had their hospitals. These only provided essential medical services. My father suggested to MKK that FACT take the initiative for a super speciality hospital that could be formed under a trust formed by the major public sector companies. That was how a trust hospital was started.

Nearly a dozen leading medical practitioners were approached to take charge of the hospital. They all declined, preferring to take care of their thriving practices. Finally, the choice fell on this doctor, who did not have much of a practice to be proud of but had excellent business acumen. This doctor would eventually turn the hospital into a personal fiefdom.

This doctor had links with a racket that facilitated medical college admissions by fraudulently falsifying mark lists of the qualifying examination. Someone had to countersign the falsified documents. In MKK’s son’s case, MKK himself did it. I believe he did this in good faith and that the culprit was the doctor himself. When the case of the doctor’s son’s medical admission with the help of falsified documents came to light, he also let the investigators know that MKK, too, was involved. This would have helped him soften the limelight on him.

MKK found himself in an unenviable situation. No father would want to indict his son to save himself. In my father’s words, this case affected MKK personally and damaged his reputation. But he stoically overcame these difficulties.

Death

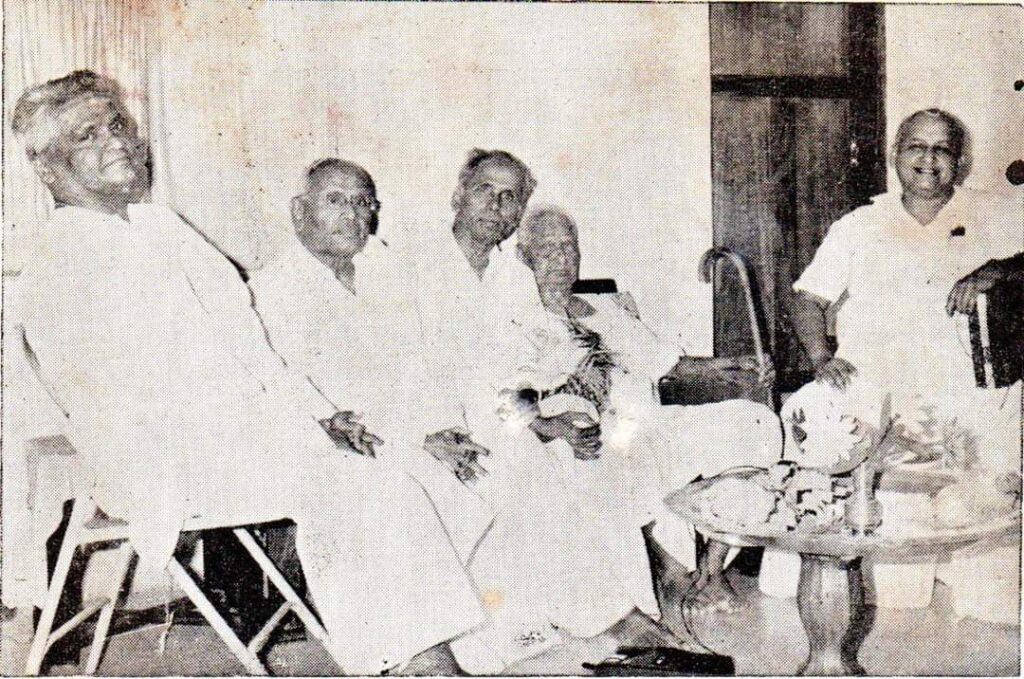

Around 1986, MKK was diagnosed with cancer of the pancreas, resulting in obstructive jaundice, one of the most painful medical conditions ever known. When I last met him with my father, the pain was not visible on his face, but he had become skinny and weak, and the smile had vanished. He seemed no longer the MKK I had known for over two decades. Eventually, MKK succumbed in September 1987. He was 67.

Pappu was still around, looking down at the visitors in his quiet majesty, having crossed 20, unusually long for a Pomeranian.

Lasting memories

What are my enduring images and memories of MKK? A profoundly religious MKK engaged in hours of puja and doing a shayana pradakshina – a circumambulation of the sanctum sanctorum while lying prostrate – at Sabarimala. An MKK who always beat me in chess. A kathakali and music aficionado enjoying and sharing their intricate insights. A repository of anecdotes from his younger days, military youth, and official days. An MKK who could converse confidently on equal terms with any industrial leader from JRD Tata onwards. Some of the other aspects require a longer discussion.

Inerasable is the memory of a man who went far beyond his remit in FACT and left his mark in the world arts, sports and cultural spheres, not just in FACT and Kerala, but even beyond. These are discussed separately below.

An elopement

While studying in Madras, he appeared in a song and dance sequence for a few moments in Gnanambika, only the second Malayalam film, released in 1940. Done to humour an acquaintance, the scene involved a lightly clad lady dancing in a pub and pouring an aperitif into a glass held up by MKK. The final film version was more erotic than it seemed when the scene was shot.

As ill luck would have it, even before MKK returned home for his next vacation, the film reached Trivandrum and did its rounds. An uncle whose daughter had been arranged for a long time to be married to MKK turned hostile. Her home in Vanchiyoor was not far from MKK’s in Palkulangara. MKK eventually called out Soudamini and made her his wife without much by way of ceremony.

Bhilai, the original Dubai

I remember an MKK who, even while working in Bhilai, did not forget to help people known to him in faraway Kerala, then as much as now, a perennial source of educated young men looking for jobs. Thus, in the 1950s, Bhilai became the original Dubai for many young Malayali men.

The good Samaritan

I remember an MKK who always entertained requests for help, even at the height of his troubles. While I was at his Ernakulam home, an accomplished badminton player of the sixties approached MKK for admission to higher studies in MD for herself and her husband. I am sure he would have done the best he could.

There was the case of a well-known Malayalam litterateur who was incidentally introduced to MKK by my father. This writer passed away in his late 40s. A good friend informed me that MKK helped the family liberally despite his troubles. These are just a few instances that I could recall. I am sure there must be many more.

For whatever he did, MKK never expected anything in return. When T Padmanabhan once asked him why he was going out of the way helping one particular undeserving person, MKK replied, he is just another fellow traveller, let him also benefit. That also explains why he worked in FACT for an unusually long stint of 12 years, knowing fully well that it was not in the best interests of his career, ignoring suggestions of many like my father that he return to his parent Madras cadre or go back to Delhi. It was also nothing but genuine love for the country that made him turn down offers from the World Bank. An unstinted faith in the public sector also made him refuse offers from private sector giants such as Tata Chemicals.

My brother

My mother used to say my father had a rough edge in his interactions with people. She added that MKK’s outlook and training changed my father from a rough person in his younger days into a more rounded personality with varied interests. Instances of MKK’s persona touching the lives of many others are legion.

When he was five, my younger brother drew an oil painting of MKK. The picture clearly showed a large belly and a small head at one end, the neck invisible, and spindly limbs merging with an obscure background. My brother titled the painting ‘M.D. Uncle’. MKK was so taken in by this five-year-old’s abstract creation that he got it framed and hung it in his bedroom, where it remained until his death.

When MKK came home once, my brother’s final exams were near. As was usually the case with my brother, his textbooks had gone missing. MKK, the large-hearted man he was, argued for my brother, suggesting that he must have donated the books to one of his poor classmates. I found this an excellent case of positive thinking, taking the sides of someone who had otherwise become a subject of ridicule and criticism.

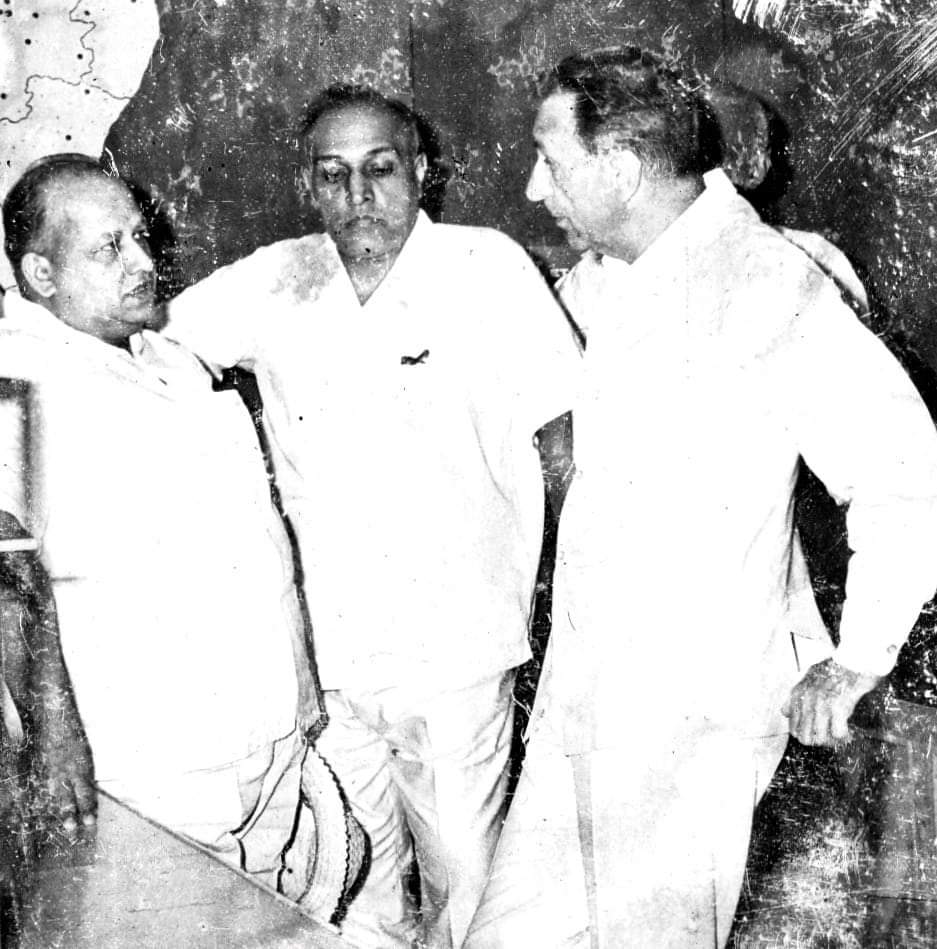

MKK the Leader

My father’s favourite leadership quote was that of Andrew Carnegie, the father of the American steel industry. When Carnegie was asked what he would like to have as his epitaph, he replied immediately: “Here lies a man who was wise enough to bring into his service men who knew more than he.” These words are quite apt in the case of MKK, as we will see below.

MKK brought under his service several outstanding people from different walks of life: able administrators and experienced and skilled engineers who helped establish new plants as well as FACT Engineering and Development Organization (FEDO) and FACT Engineering Works (FEW). He brought a young Charles Correa to design an aeroplane-shaped Ambalamedu House long before he became famous as Chief Architect of New Bombay.

From sports, there was Balan Pandit, the first Keralite to play county cricket and make it to India 16; S. Ramanujan, Kerala Table Tennis champion for a decade; international volleyball star T.D. Joseph alias FACT Pappan, Olympian footballer Simon Sunderraj, who scored India’s last goal in the 1960 Olympics; Kesavan Nair, who taught me the basics of swimming and later became the national swimming coach; and TKS Mani, who brought Kerala its first Santosh Trophy in football.

FACT’s sports infrastructure and coaches produced eminent badminton players such as Noreen Padua, Jessie Philip, and many others. The Udyogamandal Club would retain its preeminent position in badminton long after MKK left.

For the FACT High School, MKK brought in Dr KNP Nayar as the principal, whose famous students at Doon School included one Prime Minister. From the world of art and literature, there was M.V. Devan, an eminent painter, sculptor, and architect, and T. Padmanabhan, an eminent Malayalam short story writer.

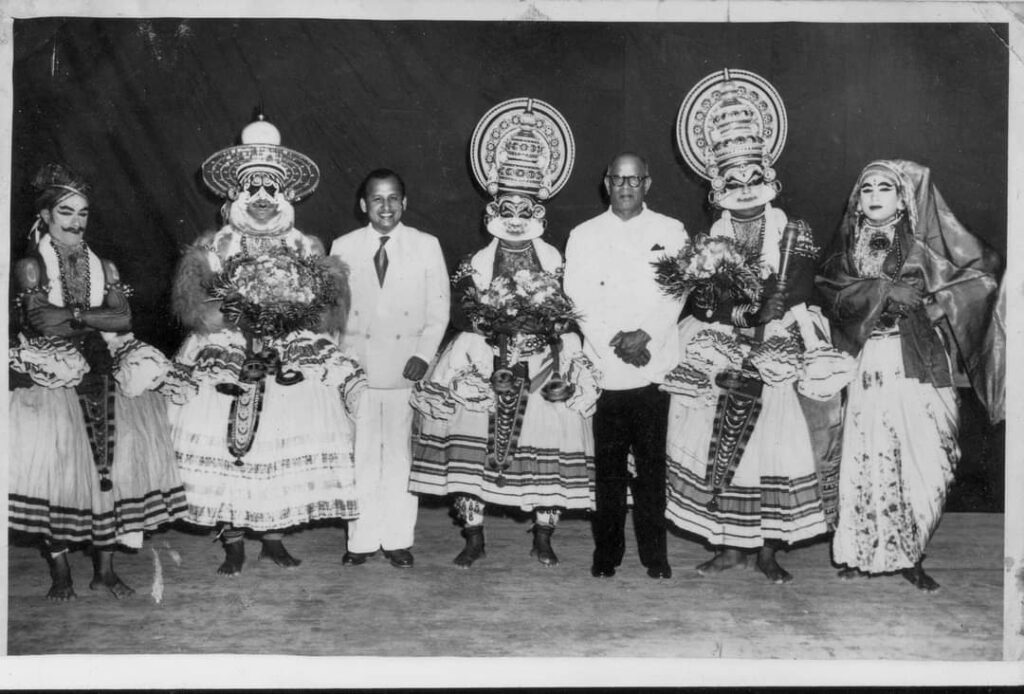

MKK and Kathakali

Contributions

My father believed that MKK’s contribution to Kathakali in the second half of the 20th century was on par with or even more significant than that of the great Malayalam poet Vallathol Narayana Menon in the first half of the century. Vallathol ensured that the art form did not die down and established Kerala Kalamandalam and the infrastructure for its future growth. MKK secured, for the best exponents of the art form, not only sustained international exposure and recognition but also financial independence and self-esteem.

My experience

During my school days, I remember aimlessly wandering through various rooms of the Udyogamandal Club. In one room, I remember seeing MKK explaining Kathakali characters and their nuances to dignitaries from other countries.

I remember MKK discussing the finer points of Karnashapatham, the Kathakali play, with Mali Madhavan Nair, its author, during its finalisation. The play incorporated ragas hitherto unused in Kathakali and modern theatrical devices such as Kunti Devi walking in from the audience.

CSR ahead of time

Advancing CSR forward more than two generations before it became a corporate motto, MKK established the FACT Kathakali School with the help of Kathakali masters Kudamalur Karunakaran Nair and Kalamandalam Karunakaran, Kathakali singers Hyderali and Sankaran Embrandiri, Chenda exponent Kalamandalam Keshavan, Maddalam artistes Chalakudy Nambisan and Kalamandalam Sankara Warrier, all of whom in turn trained many others including Mohanan, Padmanabhan, Jayadeva Varma, and Bhaskaran, and the list goes on…

Foreign tours

Foreign tours for Kathakali troupes had taken place even during Vallathol’s time, but MKK took it to a higher level. His efforts undoubtedly ensured that Kathakali’s reputation as a total theatre remained enshrined for centuries. He arranged numerous such visits using his contacts and ensured their comforts were well cared for. There was an odd instance of one troupe losing their luggage and MKK throwing in his weight to ensure they were not inconvenienced and that their engagements took place on time.

Personal help

MKK went out of the way to help many Kathakali performers. My father, who knew about many of them through my maternal grandfather, a doctor and Kathakali fanatic, warned MKK against helping the undeserving. MKK, of course, ignored such advice. For one such prominent beneficiary, MKK got jobs for his wife, daughter, and son-in-law. He ensured that his house construction near Ernakulam was smoothened by ensuring steel and cement inputs at lower-than-market rates. MKK worked hardest to ensure he won national recognition and worldwide fame.

My father never liked this particular actor for different reasons. Once visiting his father-in-law’s (my maternal grandfather’s) house in Alleppey, he walked into my grandfather’s room. Apart from being a medical professional, my grandfather was a Kathakali afficionado who had my mother trained in Kathakali for four years. He maintained separate private quarters in his house, accessible day and night without disturbing family members. He was also known for assisting various people, including musicians and Kathakali performers. My father saw this actor sprawled out on my grandfather’s spring cot. My father’s dislike for him was, therefore, for taking undue advantage over and above what was deserving.

Fed up with his excessive demands, T Padmanabhan once asked MKK whether he should comply with such unreasonable demands. MKK replied, “Give, give, give whatever he asks for. Such actors come only once in a generation or two.”

Not surprisingly, this actor did not care to pay his last respects to MKK after his death, even though he was available in Trivandrum. When my father told me this, I couldn’t help but remember Pappu, who remained with MKK through thick and thin, living for an unusually long twenty-plus years, as worthy of more tremendous respect.

Krishna Menon and MKK

VK Krishna Menon, about whom I had written earlier, (also this blog), was one for whom MKK had unstinted admiration. A few days before Menon passed away in October 1974, MKK called on him at his residence near Teen Murti House in New Delhi. MKK recalled this meeting in his memoirs (With Grudge Against None). Krishna Menon was aware of the cases against MKK. He held MKK’s hands, weakly smiled and said, rather meaningfully, “From the time of Ramayana, our country’s tradition has been to reject the most faithful.” How apt those words were can be gauged from the fate of Krishna Menon himself, who had laid the foundation of the Indian defence sector and was the Indian face in the UK for two and a half decades before independence, almost singlehandedly in charge of turning British public opinion in favour of freeing India.

By way of conclusion

MKK’s soul, wherever it is, I am sure, is happy and content. He might sometimes be looking at those who made him happy, and even those who had troubled him, and laughing away from the depths of his heart, without any grudge or ill-will, ahahaha …

Footnote: In September 1987, after MKK’s death, my father requested that I write an article on him, as he was unable to. My father passed away a year and two months later. I am fulfilling that promise given to him 33 years later with this piece. An earlier and much shorter version, written in Malayalam, was published earlier in an online journal.

(All photographs are courtesy of Gopinath Krishnan, eldest son of MKK Nayar. I am also thankful to him for clarifying specific points. Brief excerpts from MKK’s memoirs titled “Aarodum Paribhavamillate” are from its English Translation by Gopakumar M. Nair, “The Story of an Era Told Without Ill-Will”.)

Note: I extensively rewrote and edited this post on 8 October 2024.

(c) G Sreekumar

![]()

From M K K Nair to Metro Sreedharan there is a gallaxy of stalwarts from the South who made India’s public sector organisations and government-owned establishments proud. Their contribution to the nation’s economic growth and industrial development is not recognised adequately. Some of the individuals were not even able to live a life commensurate with their positions at the time of their retirement.

From M K K Nair to Metro Sreedharan there is a gallaxy of stalwarts from the South who made India’s public sector organisations and government-owned establishments proud. Their contribution to the nation’s economic growth and industrial development is not recognised adequately. Some of the individuals were not even able to live a life commensurate with their positions at the time of their retirement.

Extremely excellent article. Eventhough many facts are known to people, this article seems to be a well worded consolidation of all such information. Worth translating to Malayalam and publish so that it will be useful to next generation laymen of Kerala as well.