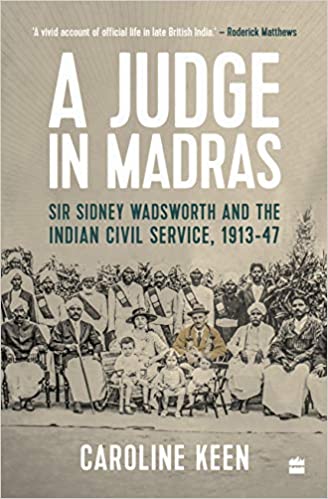

Caroline Keen, A Judge in Madras: Sir Sidney Wadsworth and the Indian Civil Service, 1913-47, Harper Collins, 2021. Rs. 699.

Most British (and Indian) officers of the Indian Civil Service diligently maintained copious diaries filled with detailed accounts of their working life in India with the hope of turning them into one or more books after retirement. Only a few of them successfully sustained the habit throughout their service. Fewer still turned them into books. One of those who wrote a manuscript after retirement, but never published it, fearing lack of demand and publisher interest, was Sir Sidney Wadsworth. Born in 1888, Wadsworth joined the ICS in Madras in 1913. Also posted to Madras, from the same batch, was Benegal Rama Rau, later Governor, Reserve Bank of India. Sidney retired in 1947 to the Isle of Man, where his father in law, Sir Robert Clegg ICS, also of Madras, spent his last years. “A Judge in Madras” is based on the draft memoirs of Sir Sidney Wadsworth.

How the book came about

In 2009, Simon Wadsworth, Sidney’s grandson, idly googling for his grandfather, chanced upon a record of the manuscript lying in the Library of the Centre for South Asian Studies at Cambridge University. Nobody in the family knew of its existence. He managed to get a copy of the manuscript. Finding it interesting, but lacking the contextual knowledge to appreciate it, he took it up with Caroline Keel, an old friend working on Indian history. She was finishing two books on British India. She took up the project of converting the manuscript into a book. ‘A Judge in Madras’, an account of Wadsworth’s 35 years in Madras Presidency till Indian independence, is the outcome.

Sidney Wadsworth

Son of a Methodist minister, Sidney was educated at Sorbonne and Cambridge, before he joined the ICS. His first posting was as Sub Collector, Vellore. He served later in Madras during the First World War. Gudur, Madanapalle, Godavari forllowed before coming back to Madras as Secretary, Board of Revenue. He was also secretary to the Governor of Madras, and the Duke of Connaught. Switching to the judicial wing, he was District Judge in Chingleput, Madura, and Chittoor. In Chittoor, he also oversaw work relating to Bangalore and Coorg. His last twelve years were at the High Court of Madras. During this period, he lived in Cottingley on Anderson Road, now the Office of the British Deputy High Commission.

Anecdotes

Keen makes the book come alive with interesting anecdotes covering the entire career of Sidney Wadsworth. There is much to learn about Madras and rest of the Presidency even for keen followers of its history. The book provides detailed accounts of motoring to Kodaikanal, visit to the Periyar dam, war time precautions in Madras, and life in various parts of Madras. There are insights into the working of the judiciary in India, the civil service, and the life of various communities such as Kallars and Chettiars. His description of the average Indian clerk or junior official, though educated and articulate, as at a loss in the absence of a ‘precedent’ in disposing of a case is apt.

There is also a vivid description of jallikattu. In the opinion of Sidney Wadsworth, there is ‘nothing which could be described as cruelty… One came away … with the feeling that one had witnessed a clean and manly sport which calls forth the best qualities of an ancient and virile race.’

It is difficult to pick one favourite anecdote from the book. So much so one has a sense of loss at what the author might have left out from the manuscript. A sensational case of the period was that of Adinarayana Rao. He fancied himself as a messiah in the style of Jiddu Krishnamurti. He produced forged certificates from Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater to support his semi-divine status. Investigations soon exposed the fraud. But, the new messiah went on to commit a few murders.

An Armenian’s Will

There were the troubles in dealing with the strange will of an Armenian merchant of the mid-18th century. He had desired that his wealth accumulate for sixty years after his death before distributing it. Two lawyers, from Istanbul and Beirut, claimed to represent over fifty heirs each from across the world. The estate included a few houses which could not be located. Then there was money with an Italian bank which wound up years back.

Complicating matters further was the language for the proceedings. The Court could not use the half dozen Armenians in the city who were with either of the camps. The lawyers claimed knowledge of Arabic and Turkish. But, the only Muslim clerk in the Court who knew Arabic could not make himself intelligible to them. A Muslim schoolboy of Turkish descent on his mother’s side proved unequal to the task of translating complicated legal matters. The court proceedings in multiple languages and accents degenerated into a real time comedy attracting many loungers from the corridors.

Then there was the case of fraud filed by a nephew against Raja Sir Annamalai Chettiar regarding the former’s estate. This required knowledge of the Chettiar style of accounting, of which Sidney had no knowledge. The case involved transactions across countries, each a separate case in itself. The supporting documents containing voluminous correspondence and account statements, ran into a frightening thirty-two volumes.

Owner of Guindy Race Course

Two other instances are personal favourites worth quoting. The first was that of an issue that came to Sidney Wadsworth as Registrar of the High Court. It

“arose from the activities of ‘a well-known lunatic’ who was a Brahmin of a decent family and fairly well-educated but ‘obsessed with the notion that he was the rightful owner of the Guindy race-course.’ He started proceedings by prosecuting the stewards of the Race Club for criminal trespass and, when his complaint was thrown out, he drafted a fresh one ‘recapitulating the old case with embellishments and adding allegations of unnatural offences’ and with the result that this ‘remarkable grew like a snowball.’

He took it from court to court, and as each authority rejected it, the name of the magistrate concerned was added to the list of persons accused of ‘unmentionable crimes.’ By the time it reached the High Court, the list of the accused looked ‘rather like a page out of the civil list’ and Sidney felt quite honoured when his name, with that of the chief justice, was added to the schedule of offenders…”

The shape of the namam

The second related to the 250-years old feud between the trustees and priests of the Sri Devarajaswami temple at Conjeevaram. The former belonged to the Vadagalai sect of Iyengars and the latter to the Tengalai sect. The formed believed in using a V-shaped namam, and the latter a T-shaped namam. The matter flared up every ten years or so. In Sidney’s time, the shape of the namam on the temple elephant became an issue. The mahout, a Tengalai, put an offending T-shaped namam on the elephant. The trustees asked him to remove it, which he refused to do.

“The trustees then filed a suit in the local munsiff’s court where it was decided that the elephant was a Vadagalai. There was an appeal to the district judge, who refused to pass judgment on whether the elephant belonged to one sect or another as he had no jurisdiction to decide questions of ‘ecclesiastical ritual.’ This pleased neither party and the matter was taken to the High Court, which some years later came to the conclusion that the elephant, like its mahout, was a Tengalai.

… the Vadagalais raised the large sum necessary to take the case up to the Privy Council which, ‘after hearing very learned arguments, finally decided that on the true principles of law, the elephant was, like the trustees, a Vadagalai.’ The officer of the court ‘duly supervised the removal of the offending emblem from the elephant’s brow and the substitution of that which their lordships of the Judicial Committee thought proper.’ However, the very next day, although the elephant was seen marching through the great courtyard of the temple still bearing the Vadagalai namam, ‘no one could see it, for over it was draped a white cloth on which was painted an enormous Tengalai emblem.’ The battle in the courts then reconvened.”

Sidney Wadsworth on the Raj

Sidney Wadsworth did not believe that a demoractic system, as in Great Britain and America, was the appropriate one for India. The Raj had prepared the ground for democracy by ‘the gradual introduction of an elaborate system of local self-government.’ Such bodies in villages, towns, taluks and districts worked ‘tolerably well’ so long as they had official chairmen and ‘a leavening’ of official nominees. As they became entirely elective nominating their own chairmen,

“… a very rapid deterioration set in. The councils became battlefields for the local factions, the administration was stultified by corruption and the people groaned under the oppression and favouritism of their own elected representatives; … it became necessary to abolish the taluk boards, to place the detailed administration of the other bodies in the hands of executive officers appointed by the government and to stiffen up the central control over the actions of the councils by a system of surcharge and suspension.”

On assessing British rule in India, Sidney felt that there would be criticism ‘not for our alleged oppressiveness or for our unwillingness to surrender power to Indians, but for the timidity and conservatism of our social and economic policies, for the excessive legalism of our system of justice and our narrow and theoretical approach to the problems of education.’ Further blame could come

“for bolstering up the medieval anachronisms of the native states, for our reluctance to tackle the social abuses connected with religious customs and institutions, for our slowness in realising that industrial development and a less pennywise attitude towards irrigation were the real cures for India’s poverty, for the way in which we have confounded the rule of law with the tyranny of a sterile legalism and for the policy which has raised up an excess of clerks and lawyers instead of a sufficiency of educated merchants, technicians and manufacturers. The historian of the future will make merry over the spasmodic nature of parliament’s control over Indian affairs and the a priori dogmatisms of some of our more famous secretaries of state.”

Conclusion

Keen acknowledges that the core of the book is the Wadsworth memoirs. But, she does not mention and nor does Sidney’s grandson in his introduction, that the memoirs was titled ‘Lo, The Poor Indian’. Nor is there a mention that the 21 chapters in the book is, barring two exceptions, along the same lines as the manuscript. And that includes the chapter titles. So, the author perhaps did not leave out any material from the original manuscript. There could have been clarity on that. It is also worth noting that Sidney had deposited in the Library, Edgar Thurston’s seven volume classic on Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Sidney obviously relied on this for his detailed account of the Kallars, Pamulas, and other tribes. But, there is no reference to this work in the list of references.

But, on the whole, Keen weaves together Sidney Wadsworth’s life in India into an engaging narrative. She puts the original manuscript into its socio-cultural context, linking them with historical, political and economic developments of the period. In the end, one feels like a witness to Sidney’s working life almost at first hand like a close confidante. Sidney most probably wanted to tell his story that way.

G. Sreekumar is a former central banker.

![]()